Doyo no Ushi no Hi, often translated as “Midsummer Day of the Ox,” is a unique Japanese tradition where people eat grilled eel (unagi) to beat the intense summer heat. This centuries-old custom blends seasonal wisdom, traditional health beliefs, and cultural storytelling. In this article, we’ll explore its origins, modern practices, the symbolic meaning of eating eel (and its alternatives), and how you can celebrate—even outside of Japan.

What Is Doyo no Ushi no Hi?

Doyo no Ushi no Hi, often translated as the “Midsummer Day of the Ox,” is a unique Japanese custom tied deeply to the traditional calendar and seasonal beliefs. To understand this observance, we must break down its components. “Doyo” refers to the approximately 18-day period that marks the transition from one season to the next, based on the Five Elements theory (gogyo) from ancient Chinese philosophy. “Ushi” is the Ox from the 12-animal Chinese zodiac, and “Hi” simply means “day.” Therefore, Doyo no Ushi no Hi refers to the day of the Ox during the Doyo period.

The Five Elements theory associates each season with a specific element—wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. The Doyo period is linked to the earth element, which is said to dominate during these transitions. The summer Doyo period typically ends in late July, just before the beginning of autumn, and the specific Day of the Ox varies each year depending on the lunar calendar. Because of this variability, there can sometimes be two Ox days in one Doyo period.

This day holds special cultural significance as it’s believed to be a time when the body is particularly vulnerable to fatigue and heat-related ailments. Hence, traditional dietary practices and rituals developed to help people maintain their health and stamina through the seasonal change.

Why Do People Eat Eel on This Day?

One of the most iconic traditions of Doyo no Ushi no Hi is eating unagi, or grilled eel. This custom stems from the belief that eel is highly nutritious and helps combat natsubate, or summer fatigue. Rich in protein, vitamins A, B1, B2, D, and E, and packed with omega-3 fatty acids, unagi is considered an energy-boosting superfood—perfect for enduring Japan’s notoriously humid summers.

Interestingly, the tradition also owes much of its popularity to a savvy Edo-period marketer named Hiraga Gennai. In the 18th century, Gennai suggested that a struggling eel vendor advertise his product as being particularly effective on the Day of the Ox. This clever bit of marketing took root, and the tradition has endured ever since. The letter “u” (as in “unagi”) is associated with stamina-boosting foods during Doyo, leading to a broader belief in consuming foods starting with “u.”

Symbolically, eel represents vitality and endurance, qualities that people wish to cultivate during the exhausting midsummer period. Its slick texture and deep flavor also make it a luxurious seasonal treat, enjoyed not just for its health benefits but also as a culinary experience.

The History and Evolution of the Custom

The origins of Doyo no Ushi no Hi go back to the Edo period (1603–1868), a time when Japanese society began to embrace seasonal health practices and ritualized food traditions. Hiraga Gennai’s successful campaign to promote eel consumption laid the groundwork for what would become a staple of Japanese summer culture.

Over time, the tradition spread across Japan, and regional variations in preparation developed. For instance, in the Kanto region (which includes Tokyo), eel is split down the back, steamed, and then grilled—a process that results in a tender texture. In Kansai (including Kyoto and Osaka), eel is cut from the belly and grilled without steaming, giving it a crispier finish and bolder flavor.

The holiday’s date changes yearly based on the traditional lunisolar calendar. Some years even feature two Days of the Ox within the Doyo period, doubling the chance for eel feasts. What began as a practical, medicinal practice has now become a beloved seasonal event observed widely throughout the country.

Modern-Day Celebrations and Where to Try It

Today, Doyo no Ushi no Hi is celebrated not just at high-end restaurants but also at homes and convenience stores. Popular eel chains and local eateries prepare special unagi meals weeks in advance. You’ll see banners, flyers, and in-store promotions highlighting the day. Grocery stores stock ready-to-eat unagi, and convenience stores release seasonal bento boxes to make the celebration accessible to all.

For those traveling in Japan in late July, major cities offer some of the best eel experiences. Tokyo’s restaurants near Ueno or Asakusa, Kyoto’s Nishiki Market, and Nagoya’s famous hitsumabushi specialty shops are top destinations. It’s wise to make reservations during this time, as spots fill up quickly due to the holiday’s popularity.

Whether you’re joining a festival, sitting down at a riverside unagiya (eel restaurant), or grabbing a convenient meal-to-go, the day offers an immersive cultural experience that beautifully blends food and seasonal mindfulness.

How to Celebrate Doyo no Ushi no Hi Outside Japan

Even if you’re outside Japan, you can still celebrate Doyo no Ushi no Hi in a meaningful way. Many Japanese or Asian restaurants in major U.S. cities—like Los Angeles, New York, and San Francisco—feature seasonal eel dishes around this time. If you’re up for cooking, frozen or canned unagi is widely available in Japanese grocery stores.

For those with dietary restrictions, alternatives like chicken, kamaboko (fish cake), or chikuwa (tube-shaped fish paste) are sometimes used as more accessible substitutes. These ingredients can be prepared in a kabayaki-style sauce to mimic the flavor and experience of unagi.

And for pronunciation? Try saying it like this: “doh-yo no oo-she no hee”. Practicing the phrase adds an authentic touch to your celebration and deepens your cultural connection.

Is Eating Eel Ethical? Environmental Concerns and Alternatives

While eel may be a beloved delicacy, it’s important to acknowledge the growing concerns over its sustainability. Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica) is currently listed as endangered due to overfishing and habitat loss. Farming eels also poses ecological challenges, as they are typically harvested from the wild and raised in captivity, disrupting natural populations.

This has led to an ethical debate around whether it’s appropriate to continue the tradition in its current form. Fortunately, alternatives are becoming more popular. Plant-based versions, such as grilled eggplant or tofu shaped and seasoned like eel, offer environmentally friendly ways to honor the tradition. Some restaurants in Japan and abroad now offer these options to meet the demand of eco-conscious consumers.

Celebrating responsibly doesn’t mean abandoning the custom—it means adapting it with awareness and respect for the planet.

How to Eat Unaju (Grilled Eel over Rice) and Make It at Home

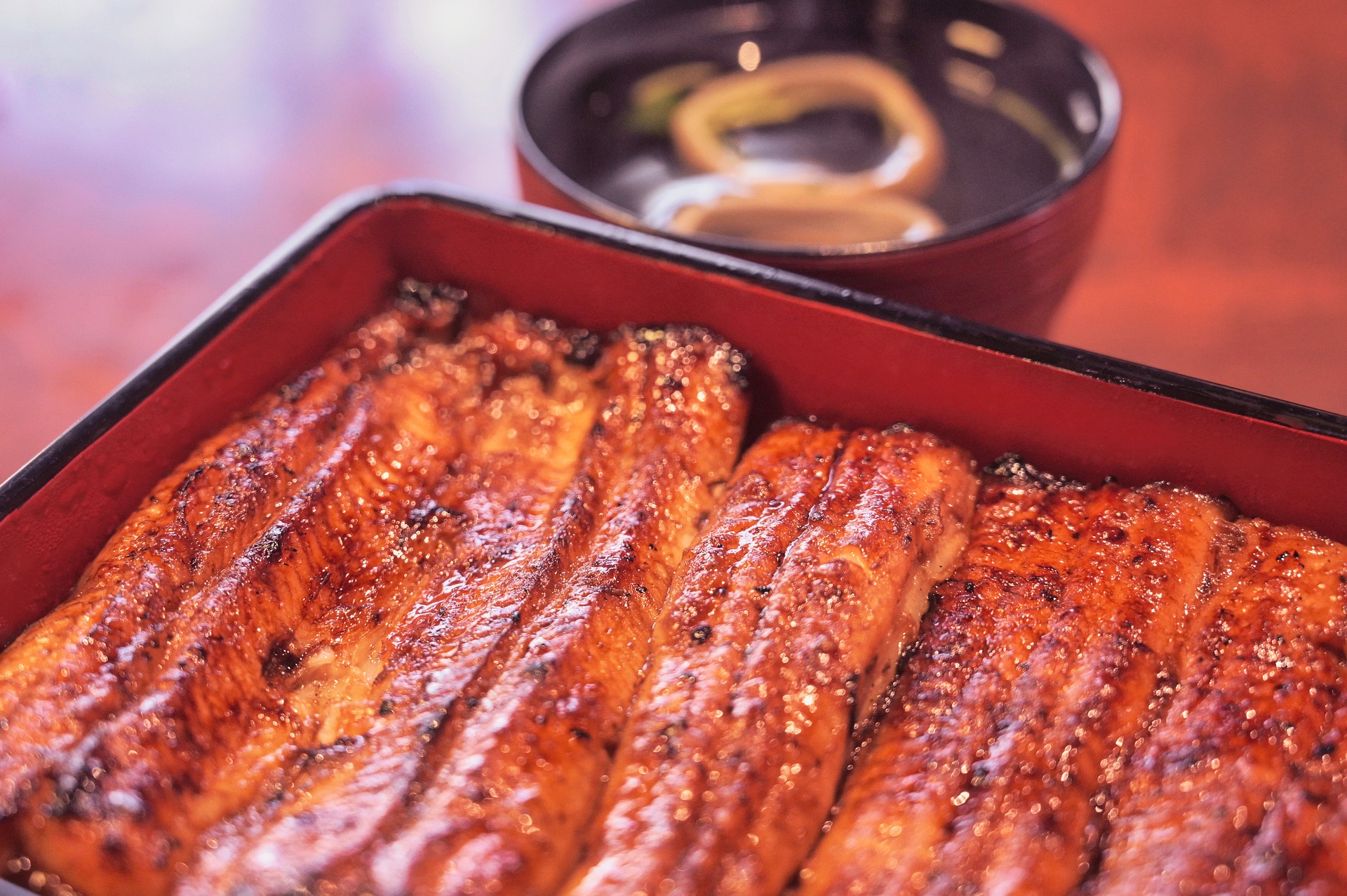

One of the most popular dishes served on Doyo no Ushi no Hi is unaju—grilled eel served over rice in a lacquer box. Another variation, hitsumabushi, is a specialty of Nagoya and offers a multi-step eating process: you first taste the eel as-is, then with condiments, and finally with a broth poured over it like ochazuke.

When eating unaju, it’s customary to sprinkle a pinch of sansho (Japanese pepper) for added flavor and digestion aid. Presentation also matters—serving it in a lacquerware box enhances both the visual and tactile experience.

To make it at home, you can use pre-packaged eel available at Asian supermarkets. Heat it gently, place it over hot rice, and drizzle with tare sauce (a sweet soy-based glaze). For plant-based versions, marinate thick slices of eggplant or tofu in a similar sauce and grill until golden. Serve it beautifully with garnishes like shredded nori or sansho for a complete experience.

Traditional Foods Besides Eel: Other “Doyo” Delicacies and Fun Trivia

While eel is the star of Doyo no Ushi no Hi, it’s not the only food traditionally enjoyed. Other stamina-boosting foods that start with “u”—like udon (thick wheat noodles) and umeboshi (pickled plum)—are also commonly consumed. Shijimi (freshwater clams) are favored for their liver-cleansing properties, especially during the hot season.

Some regions enjoy doyo mochi (sticky rice cakes), doyo tamago (eggs eaten for strength), and other local specialties. Although usagi-nabe (rabbit hot pot) is mentioned in some sources, it is not a widely recognized or mainstream tradition for this day.

The underlying belief is to eat nourishing and easily digestible food that helps the body transition smoothly into the next season.

Fun fact: there can be more than one Day of the Ox in a single Doyo period, giving people another chance to enjoy their favorite summer foods. And in recent years, the tradition has evolved with modern marketing—convenience stores now offer mini unaju sets, and social media buzzes with photos of lavish eel dishes.

Final Thoughts: A Tradition That’s More Than Just a Meal

Doyo no Ushi no Hi is more than a day to eat grilled eel—it’s a reflection of Japan’s deep connection to seasonal rhythms, traditional health practices, and cultural identity. What began as a practical response to summer fatigue has grown into a widely celebrated ritual that blends food, folklore, and philosophy.

Whether you’re in Japan or celebrating from afar, Doyo no Ushi no Hi invites you to embrace the season mindfully. By learning its history and enjoying its traditions—whether through a bite of unagi or a plant-based alternative—you take part in a living heritage that continues to nourish the body and spirit alike.