Shirasu, a beloved ingredient in Japanese cuisine, refers to tiny juvenile fish, mainly ma-iwashi (Japanese sardine) and katakuchi-iwashi (anchovy). These nutrient-rich fish are often eaten raw, boiled, or dried and are deeply rooted in Japan’s coastal food culture. Sometimes, other juvenile fish or small sea creatures may also be found mixed in. Whether you’re visiting Japan or simply curious about Japanese ingredients, this guide will help you understand everything about shirasu.

What is Shirasu?

Shirasu is the Japanese term for juvenile whitebait, particularly the young of fish like ma-iwashi (Japanese sardine) and katakuchi-iwashi (anchovy). These baby fish, usually less than 2 centimeters in length, are harvested from Japan’s coastal waters and have long been a staple in regional cuisine. Depending on the season and catch, shirasu can sometimes include other small sea creatures like juvenile squid or sand eels. In Japan, its popularity is rooted in its delicate umami flavor, nutritional value, and versatility across cooking methods. Shirasu is especially prevalent in seaside regions like Shizuoka and Kanagawa, where it’s not only consumed fresh but also plays an integral role in local dishes and food culture.

Types of Shirasu and How They Differ

There are four main types of shirasu, each distinguished by how they are processed:

- Nama Shirasu (raw shirasu): Ultra-fresh and perishable, these are often consumed on the same day of the catch.

- Kamaage Shirasu (boiled shirasu): Lightly boiled without added salt, soft and mildly sweet.

- Shirasu-boshi (lightly dried shirasu): Partially dried, preserving moisture while enhancing flavor and shelf life.

- Chirimen Jako (fully dried shirasu): Thoroughly dried, firm in texture, and with a higher salt concentration.

| Type | Texture | Taste | Appearance | Salt Content | Shelf Life |

| Nama Shirasu | Soft, slippery | Mild, ocean-fresh | Translucent white | Low | 1 day (refrigerated) |

| Kamaage Shirasu | Soft, fluffy | Lightly sweet | Opaque white | Very low | 2-3 days (refrigerated) |

| Shirasu-boshi | Chewy, moist | Umami-rich | Slightly shrunken | Medium | 1 week (refrigerated) |

| Chirimen Jako | Dry, crunchy | Intensely savory | Firm and shriveled | High | Several weeks (cool, dry place) |

The primary difference between shirasu-boshi and chirimen jako lies in the moisture and salt levels. Shirasu-boshi retains more moisture, offering a chewier texture, while chirimen jako is fully dehydrated and preserved.

How Shirasu is Eaten in Japan

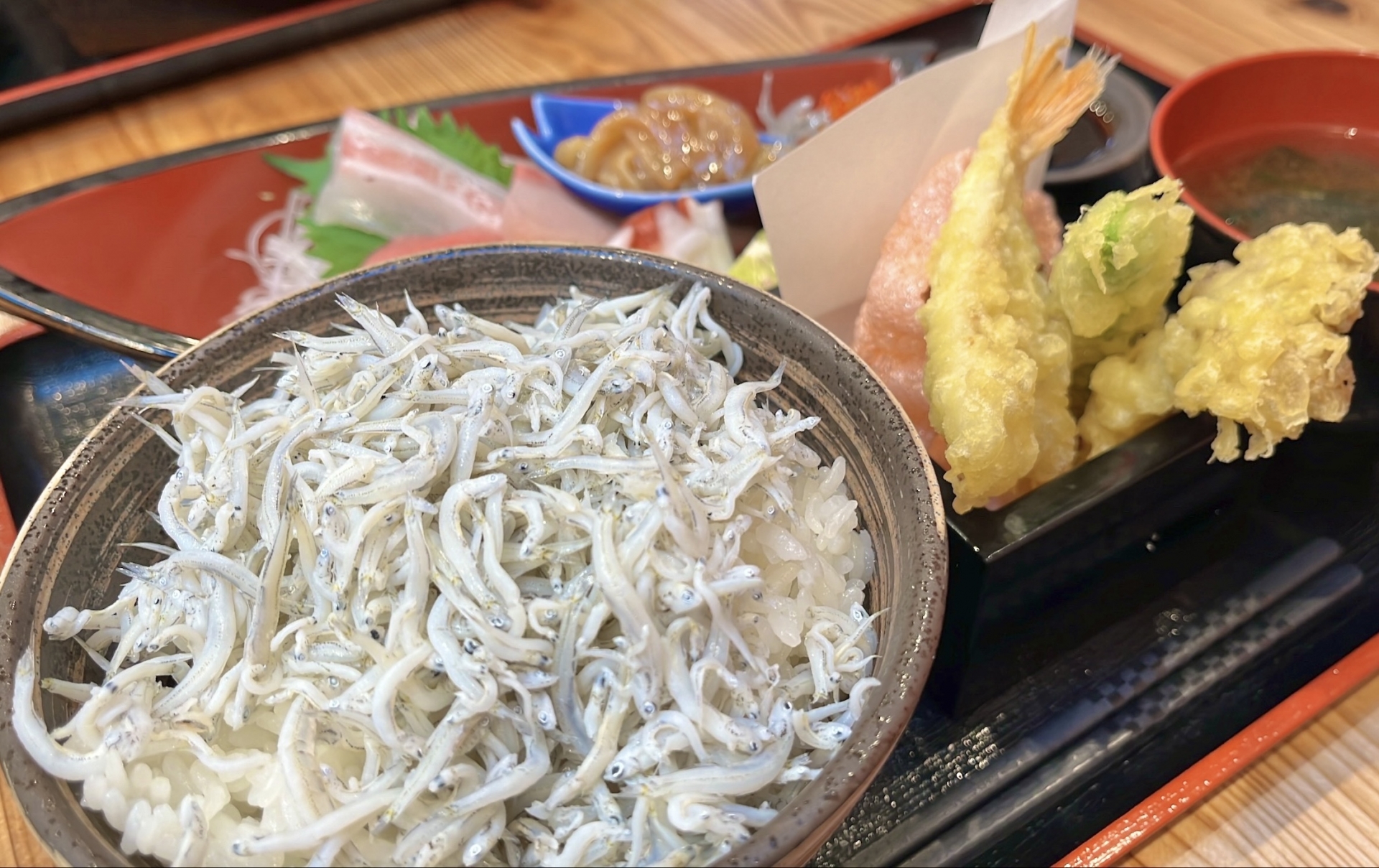

Shirasu is a beloved ingredient in everyday Japanese meals. Among the most popular uses is shirasu-don, a rice bowl topped with a generous serving of shirasu—sometimes mixed with grated daikon, soy sauce, or a raw egg yolk.

Tamagoyaki with shirasu, a rolled Japanese omelet with bits of boiled or dried shirasu folded in, offers a protein-rich breakfast or side dish. In modern Japanese fusion, chefs incorporate shirasu into pasta, creating East-meets-West plates with garlic, olive oil, and chili pepper.

Shirasu sushi, such as gunkan maki (battleship roll) or nigiri, is also popular, especially with nama shirasu. Due to its high perishability, raw shirasu is only available close to the coast and must be consumed on the same day it’s caught.

Regional Specialties Featuring Shirasu

Certain coastal regions are renowned for their shirasu dishes:

- Enoshima: One of the best-known destinations for fresh nama shirasu. Restaurants like Tobiccho serve shirasu-don with local seasonal variations, drawing both locals and tourists.

- Shizuoka: A leading producer of kamaage and shirasu-boshi, Shizuoka’s markets and eateries serve a variety of regional favorites.

- Kamakura: Known for its shirasu-based snacks and street food, Kamakura also celebrates the nama shirasu season, typically from spring to early autumn.

Spring through early autumn is the peak season for nama shirasu, offering travelers a chance to enjoy this delicacy at its freshest.

Health Benefits of Shirasu

Shirasu is not just flavorful—it’s also a powerhouse of nutrition. A 100-gram serving offers:

- High-quality protein: Essential for muscle and tissue repair.

- Calcium: Important for bone health, especially when eaten whole with bones. For most people, the bones are soft and not a concern.

- Omega-3 fatty acids: Promote heart health and reduce inflammation.

- Vitamin D: Aids in calcium absorption and immune function.

- Vitamin B12: Supports nerve function and red blood cell production.

However, health-conscious consumers should also be aware of certain considerations:

- Sodium levels: Dried forms like chirimen jako are high in salt.

- Purines: Present in small fish, which may affect individuals with gout or kidney conditions.

Shirasu is often recommended for elderly diets due to its easy digestibility and bone-strengthening calcium. While it can be used as baby food, it’s advisable to briefly blanch shirasu in hot water before serving to reduce salt and soften texture.

How to Buy and Store Shirasu Outside Japan

For those living outside Japan, shirasu can still be enjoyed with a bit of effort:

- Where to buy: Look for Asian grocery stores, Japanese supermarkets, or online specialty retailers.

- Types available: Kamaage and shirasu-boshi are more common outside Japan; nama shirasu is rarely exported due to perishability.

- Storage tips:

- Refrigerate kamaage and shirasu-boshi in an airtight container.

- Freeze if you plan to store longer than a few days.

- Store chirimen jako in a cool, dry pantry for several weeks.

Quality check: Fresh shirasu should not have an off smell or yellow tint. Look for bright, clean specimens with intact eyes and bodies.

Substitutes: In recipes, dried whitebait or small anchovies can mimic the taste and texture of shirasu.

Frequently Asked Questions about Shirasu

Can you eat shirasu raw? Yes, nama shirasu is eaten raw but must be consumed fresh on the same day. It’s typically served in coastal regions.

What does shirasu taste like? Shirasu has a mild, slightly salty, and umami-rich flavor. Fresh versions have a delicate ocean taste, while dried forms are more savory.

Is it safe for kids or pregnant women? Generally yes, especially when cooked. However, raw shirasu should be avoided by pregnant women and young children due to potential foodborne risks. Always consult a healthcare provider if unsure.

What’s the difference between shirasu and chirimen jako? Chirimen jako is a fully dried form of shirasu. It has a firmer texture, stronger flavor, and higher salt content.

Why is shirasu so salty? The saltiness comes from the drying process. Shirasu-boshi and chirimen jako have higher sodium levels to aid preservation. They’re described as “shoppai” (savory-salty), not spicy.

Conclusion: Why You Should Try Shirasu

Shirasu offers a delicious glimpse into the heart of Japanese coastal cuisine. Whether eaten fresh in a seaside town or purchased dried abroad, these tiny fish pack a surprising punch of flavor and nutrition. Their versatility spans from traditional dishes like rice bowls and sushi to innovative fusions in global kitchens.

However, freshness and salt content should be considered, especially for those with dietary restrictions. With the right preparation, shirasu can be a valuable addition to a healthy, adventurous diet.

Next time you’re exploring Japanese cuisine, don’t miss out on these tiny treasures from the sea!