The Sengoku Period, known as Japan’s Warring States era, was a time of intense military conflict, political upheaval, and social transformation. Spanning from 1467 to 1603, it marked the rise and fall of powerful warlords and eventually paved the way for the Tokugawa shogunate. This article breaks down the origins, key players, major events, and cultural evolution of this transformative period in Japanese history.

What Was the Sengoku Period?

The Sengoku Period, also known as the Warring States Period, refers to a century-and-a-half of social upheaval, military conflict, and political fragmentation in Japan. Spanning from 1467 to 1603, it began with the outbreak of the Ōnin War and concluded with the unification of Japan under the Tokugawa shogunate.

The name “Sengoku” (戦国) directly translates to “warring states,” and it echoes a similar period in Chinese history. During this era, Japan’s central authority collapsed, leading to the rise of regional warlords (daimyō) who battled for control over territories. The conflict transformed Japan’s political landscape and introduced revolutionary changes in warfare, governance, and culture.

The period ends in 1603 when Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Tokugawa shogunate, marking the start of the Edo period. Despite the chaos, the Sengoku Period laid the groundwork for modern Japan, both politically and culturally.

Why Did the Sengoku Period Begin?

The root cause of the Sengoku Period lies in the weakening of the Ashikaga shogunate. By the mid-15th century, the central government in Kyoto had become largely symbolic, with real power increasingly held by regional lords. This decentralization created fertile ground for conflict.

The immediate catalyst was the Ōnin War (1467–1477), a civil war stemming from a succession dispute within the Ashikaga shogunate. While the war itself ended indecisively, it shattered Kyoto and eroded the legitimacy of the central government. In its wake, powerful regional daimyōs seized the opportunity to expand their influence, often through military conquest.

The result was a fractured Japan, where alliances shifted frequently, and power was determined by military strength rather than noble birth. With no overarching authority to enforce order, a prolonged period of warfare ensued.

Key Figures of the Sengoku Period

Three central figures stand out in the narrative of Japan’s unification: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Known collectively as the “Three Unifiers,” their leadership, innovation, and ambition changed the course of Japanese history.

Oda Nobunaga’s Revolutionary Tactics

Oda Nobunaga (1534–1582) was a visionary and ruthless leader. He revolutionized Japanese warfare by incorporating firearms—specifically arquebuses—into his battle strategies. His victory at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575 demonstrated the effectiveness of organized gunfire against traditional cavalry charges.

Nobunaga was also a master of psychological warfare, often using fear to subdue opponents. He dismantled entrenched Buddhist power structures and built fortresses like Azuchi Castle to symbolize his dominance. Though assassinated in 1582, his legacy laid the foundation for Japan’s eventual unification.

Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s Political Genius

Following Nobunaga’s death, his former general Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–1598) consolidated power. Unlike Nobunaga, Hideyoshi was a master diplomat and administrator. He enacted sweeping land surveys, redistributed fiefs, and initiated the famous “sword hunt”—disarming peasants to reduce the threat of rebellion.

Hideyoshi also restructured society by freezing social classes and imposing sumptuary laws. His ambitions extended beyond Japan, culminating in the unsuccessful invasions of Korea (1592–1598). Though he lacked a legitimate heir, his governance created a centralized state for Tokugawa to inherit.

Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Birth of a Dynasty

Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) bided his time until after Hideyoshi’s death. His decisive victory at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 allowed him to seize control of Japan. In 1603, he was appointed shōgun by the emperor, marking the official end of the Sengoku Period.

Ieyasu’s leadership emphasized stability, hierarchy, and long-term governance. His Tokugawa shogunate would rule for over 250 years, ushering in the peaceful Edo Period. His legacy is one of patience, strategic acumen, and institution-building.

Daily Life During the Sengoku Period

While the battlefield dominated headlines, daily life for most Japanese people continued in the background. Society was structured into rigid classes: samurai, farmers, artisans, and merchants. Samurai, the warrior class, held power but often lived modestly unless affiliated with major daimyōs.

Peasants formed the majority and were tied to the land. They paid taxes in rice and were often caught in the crossfire of ongoing wars. Artisans produced goods for local markets, and merchants grew in importance despite their low status.

Women played vital but often overlooked roles. Noblewomen managed estates and occasionally led troops. Figures like Nene (Hideyoshi’s wife) and Ii Naotora demonstrate female agency in a male-dominated society.

Religion shaped daily routines and politics. Buddhism remained dominant, but Christianity gained followers—especially among the Kyushu daimyōs—due to Portuguese missionaries. Architecturally, this period saw the rise of majestic castles, blending defense with luxury.

How the Sengoku Period Ended

The Sengoku Period drew to a close with the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. Tokugawa Ieyasu’s eastern forces triumphed over the western alliance loyal to Hideyoshi’s heir. This battle decisively tipped the balance of power.

Three years later, Ieyasu was appointed shōgun by the emperor, establishing the Tokugawa shogunate. This marked a return to centralized control after over a century of chaos. The new regime implemented strict social hierarchies, alternate attendance systems, and foreign policy isolation—hallmarks of the Edo period.

Thus, the curtain fell on an age defined by war and opened on an era of peace and stability.

How the Sengoku Period Differs from the Azuchi-Momoyama Period

Although overlapping in time, the Sengoku Period and the Azuchi-Momoyama Period represent different phases of Japan’s evolution.

- Political Landscape: Sengoku was characterized by fragmentation and constant warfare. In contrast, the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573–1603) saw efforts toward unification by Nobunaga and Hideyoshi.

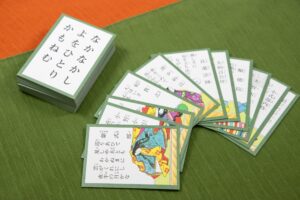

- Cultural Development: While Sengoku culture was austere and survival-driven, the Momoyama Period saw a flourishing of the arts—tea ceremonies, lavish architecture, and Noh theater.

- Architecture: Sengoku castles were utilitarian. Momoyama castles, like Osaka Castle, were grand and decorative.

- Religion & Foreign Relations: Sengoku Japan was open to foreign influence, especially Christianity and Portuguese trade. In the Momoyama period, policies began restricting these interactions.

The Legacy of the Sengoku Period Today

The impact of the Sengoku Period is still visible in modern Japan. The era reshaped military organization, governance structures, and cultural identity.

- Government: The idea of a centralized authority under a unifying leader echoes in Japan’s political continuity.

- Military Structure: Hierarchical command systems developed during the Sengoku Period influenced modern Japanese bureaucracy and even corporate hierarchies.

- Culture: The aesthetics of samurai culture—discipline, loyalty, and honor—still permeate Japanese media and identity.

Popular Culture and Modern Media

The Sengoku Period continues to captivate global audiences. Games like Total War: Shogun 2 and Nioh, and anime such as Sengoku Basara depict stylized versions of the era.

These portrayals blend historical fact with fantasy but keep interest in the period alive. Characters like Nobunaga appear as anti-heroes or visionaries, reflecting modern reinterpretations of leadership and ambition.

Lessons in Leadership from the Sengoku Daimyo

Modern Japanese and global business leaders study Sengoku warlords for strategic inspiration:

- Nobunaga: Innovator who challenged norms.

- Hideyoshi: Master negotiator and nation-builder.

- Ieyasu: Long-term strategist with vision.

Their methods are applied in leadership seminars, military academies, and management books. The chaotic environment they navigated offers timeless lessons in resilience and adaptability.

Visual Timeline of the Sengoku Period

Key Events Timeline:

- 1467: Ōnin War begins

- 1560: Battle of Okehazama (Nobunaga defeats Imagawa)

- 1575: Battle of Nagashino

- 1582: Nobunaga’s death

- 1592: Invasion of Korea

- 1600: Battle of Sekigahara

- 1603: Tokugawa shogunate established

What We Can Learn from the Sengoku Period: Conclusion

The Sengoku Period teaches us that even prolonged chaos can give rise to visionary leadership and transformative change. The values of resilience, loyalty, and strategic thinking born in this era continue to influence Japanese society, politics, and business to this day. In the dynamic conflict between ambition and survival, Japan forged not only unity but a modern identity rooted in samurai principles.

“In the chaos of the Warring States, Japan discovered the seeds of its unification—and the roots of its modern spirit.”