The Ōnin War (1467–1477) was a pivotal civil war in Japan that marked the decline of centralized authority and the rise of feudal conflict. This article explores the roots of the war, key players, the decade-long struggle, and how it led to the Sengoku Period — Japan’s infamous age of the warring states.

What Was the Ōnin War?

The Ōnin War (1467–1477) was a prolonged civil conflict in Japan that erupted during the Muromachi period, primarily fought in and around the imperial capital of Kyoto. Spanning a full decade, it was sparked by a dispute over succession within the Ashikaga Shogunate, but quickly escalated into a wider conflict involving powerful feudal lords, or daimyō, across the country. Although the war failed to produce a clear victor, it profoundly destabilized the political landscape, leading to the collapse of centralized rule and the emergence of the Sengoku Period—Japan’s infamous “Age of Warring States.”

Causes of the Ōnin War

The roots of the Ōnin War lie in the fragile political structure of the Ashikaga Shogunate and an intense succession crisis. When Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimasa failed to clearly name a successor, a power struggle ensued between factions supporting his brother, Ashikaga Yoshimi, and his infant son, Yoshihisa. This personal conflict became national in scale, as two powerful daimyō, Hosokawa Katsumoto and Yamana Sōzen, backed opposing heirs.

The rivalry between Hosokawa and Yamana went beyond succession politics. Both leaders commanded influential clans and large military forces, and their feud became emblematic of the crumbling feudal order. The inability of the shogunate to mediate the dispute exposed its weakening authority. What began as a courtly dispute turned into open warfare when Yamana’s forces entered Kyoto, sparking what would become a decade-long conflict.

Breakdown of the Shogunate’s Authority

The Ashikaga Shogunate had long struggled to maintain control over regional lords, but by the mid-15th century, its authority was essentially symbolic. Unlike the Kamakura Shogunate, which had exercised relatively strong military control, the Muromachi regime relied on delicate political alliances that eroded over time. In contrast to the later Edo period’s rigid hierarchy under the Tokugawa, the Muromachi system was fragmented and rife with competing interests.

The war revealed the systemic weakness of the shogunate. Local lords began acting autonomously, raising private armies and forging independent alliances. The central government could no longer enforce peace or law, setting the stage for a century of constant warfare. The collapse of centralized power became both a cause and consequence of the Ōnin War.

Key Events and Timeline of the War

The Ōnin War began in 1467, when Yamana Sōzen’s troops entered Kyoto in support of Ashikaga Yoshihisa. Hosokawa Katsumoto responded by mobilizing his own forces. Initial battles turned the capital into a battleground, with large sections of Kyoto burned and destroyed. Despite the scale of destruction, neither side was able to gain a decisive advantage, resulting in a prolonged stalemate.

Key Events Timeline:

- 1467: War begins in Kyoto. Battles erupt between Hosokawa and Yamana factions.

- 1468-1471: Continued skirmishes devastate the capital. Civil war spreads to surrounding provinces.

- 1473: Both Hosokawa Katsumoto and Yamana Sōzen die, leaving their factions leaderless.

- 1477: Fighting officially ends, though no clear victor emerges. Kyoto is in ruins.

This decade of war not only reduced Kyoto to rubble but also paralyzed the shogunate, giving rise to regional autonomy and fueling further conflict.

Major Figures in the Ōnin War

Hosokawa Katsumoto

A prominent daimyō and deputy to the shogun, Hosokawa was a skilled political operator. He supported Ashikaga Yoshimi and mobilized significant forces to defend his position.

Yamana Sōzen

Rival to Hosokawa and head of the powerful Yamana clan, Sōzen backed the shogun’s son, Ashikaga Yoshihisa. His entry into Kyoto triggered the war.

Ashikaga Yoshimasa

The sitting shogun during the conflict, Yoshimasa’s indecision in naming a successor was the initial spark. His weak leadership failed to contain the war and marked the decline of Ashikaga power.

Visual Aid: Clan map and simplified family tree (suggested)

Aftermath and Long-term Consequences

The immediate aftermath of the Ōnin War was political fragmentation. Kyoto, once the heart of imperial and shogunal power, was devastated and diminished. Local warlords (daimyō) filled the vacuum, entrenching themselves in their regions with private armies.

Without a strong central authority, Japan descended into the Sengoku Period (c. 1467–1600), a century of nearly constant warfare, shifting alliances, and social upheaval. The aristocracy lost power, while military leaders became the dominant force in society.

Culturally, the war caused immense destruction. Temples, estates, and historical buildings were lost, marking a dark age for Kyoto’s cultural heritage.

The Path to the Sengoku Period

The war created a power vacuum that plunged Japan into decentralized chaos. The Sengoku Period that followed was defined by:

- Constant warfare among regional daimyō

- Rise of castle towns and fortified domains

- Decline of the emperor and shogun as effective rulers

Cultural and Urban Impact of the War

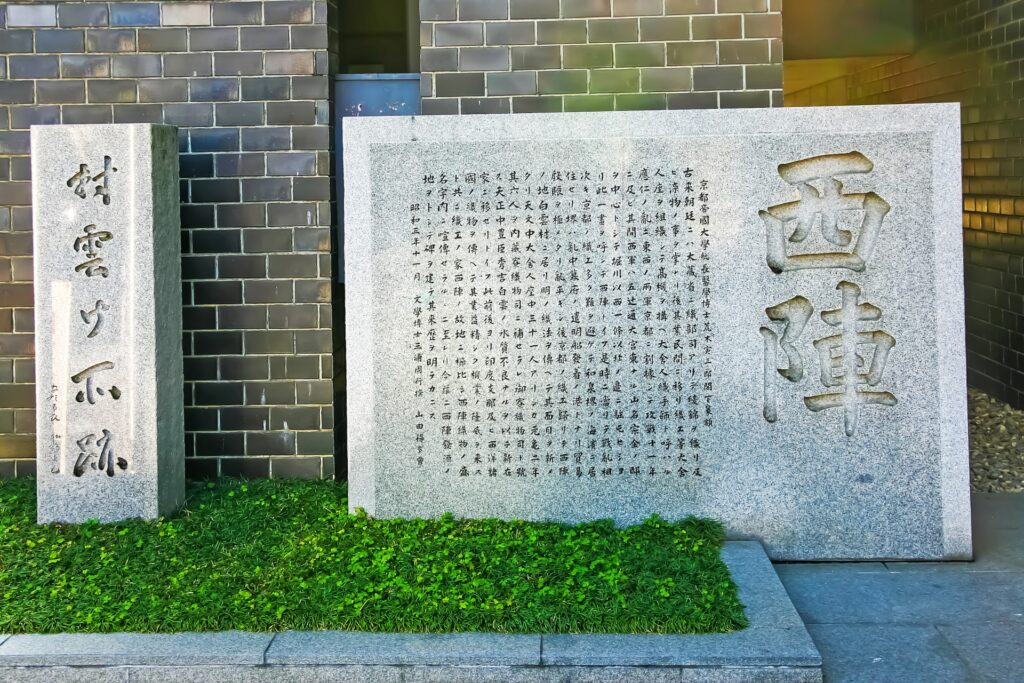

Kyoto bore the brunt of the Ōnin War. Once a center of refined court culture, the city was transformed into a battlefield. Entire districts were destroyed, including aristocratic mansions and ancient temples. The destruction disrupted not only political order but also the cultural life of the capital.

The economic cost was equally severe. Merchants fled, trade declined, and artisans lost patrons. The rebuilding of Kyoto took decades, and many cultural treasures were lost forever. Notable losses include parts of the Gozan Zen temples and several shoin-style palaces.

Visual maps contrasting pre- and post-war Kyoto could illustrate the scale of destruction.

Why the Ōnin War Still Matters Today

The Ōnin War remains a crucial turning point in Japanese history. It represents the collapse of centralized governance and the dangers of unresolved succession and factional rivalry. For modern readers, the war offers insights into how political vacuum and weak leadership can lead to societal breakdown.

In Japan, the Ōnin War is often cited as a symbolic lesson in governance failure. It serves as a historical metaphor for disunity and the perils of divided authority. Modern scholars and students alike revisit this era to understand the roots of Japan’s feudal fragmentation and eventual reunification under the Tokugawa.

FAQs about the Ōnin War

Q: What caused the Ōnin War?

A: A succession crisis within the Ashikaga Shogunate and power struggles between daimyō, particularly Hosokawa Katsumoto and Yamana Sōzen.

Q: Who were the key figures?

A: Hosokawa Katsumoto, Yamana Sōzen, and Ashikaga Yoshimasa.

Q: What were the effects of the war?

A: Political fragmentation, destruction of Kyoto, and the start of the Sengoku Period.

Q: Was the Ōnin War considered a civil war?

A: Yes, it was a civil war among rival factions within the same political system.

Q: How did it lead to the Sengoku Period?

A: By destroying central authority, the war allowed regional lords to gain autonomy and compete for dominance.

Conclusion – Lessons from the Ōnin War

The Ōnin War was more than just a military conflict; it was a profound turning point in Japanese history. Born from a succession crisis and compounded by political rivalries, it exposed the fragility of the Ashikaga Shogunate and shattered Kyoto’s status as the political center. The resulting chaos gave rise to the Sengoku Period, a century of warfare that reshaped the nation’s social and political structures.

The key takeaway is clear: internal division and weak leadership can unravel even the most established systems. For historians, students, and general readers, the Ōnin War offers a lens into the mechanisms of collapse and the long road to restoration that followed.