Katsushika Hokusai is one of the most celebrated artists in Japanese history, best known for his woodblock print The Great Wave off Kanagawa. His prolific career spanned over 70 years and produced thousands of artworks—from landscapes and birds to mythological scenes. This article explores Hokusai’s artistic journey, his unique style, lesser-known masterpieces, and how his legacy continues to shape both traditional and modern art across the globe.

Who Was Katsushika Hokusai?

Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) was one of Japan’s most prolific and influential artists, whose career spanned more than seven decades and reshaped the visual culture of the Edo period. Born in Edo (modern-day Tokyo) to a mirror-maker’s family, Hokusai began his artistic training at a young age, apprenticing under ukiyo-e master Katsukawa Shunshō. Early exposure to printmaking, combined with a fascination for Chinese painting and Western perspective, shaped his distinctive visual language.

Over his lifetime, Hokusai changed his name more than thirty times—a testament to his constant reinvention and artistic experimentation. Each new name marked a distinct phase in his creative journey. He was known not only for his technical brilliance but also for his eccentric personality. According to popular anecdotes, Hokusai moved houses over ninety times, sometimes relocating multiple times a day simply to avoid cleaning his studio. Such quirks reveal a restless, obsessive artist wholly devoted to his craft.

Hokusai lived during Japan’s Edo period, a time of relative peace, economic growth, and urbanization. The flourishing of the merchant class created new audiences for art, particularly the vibrant woodblock prints known as ukiyo-e—literally “pictures of the floating world.” Within this cultural context, Hokusai emerged as a visionary who elevated a popular art form into one of deep emotional and spiritual resonance.

Signature Works: Beyond the Great Wave

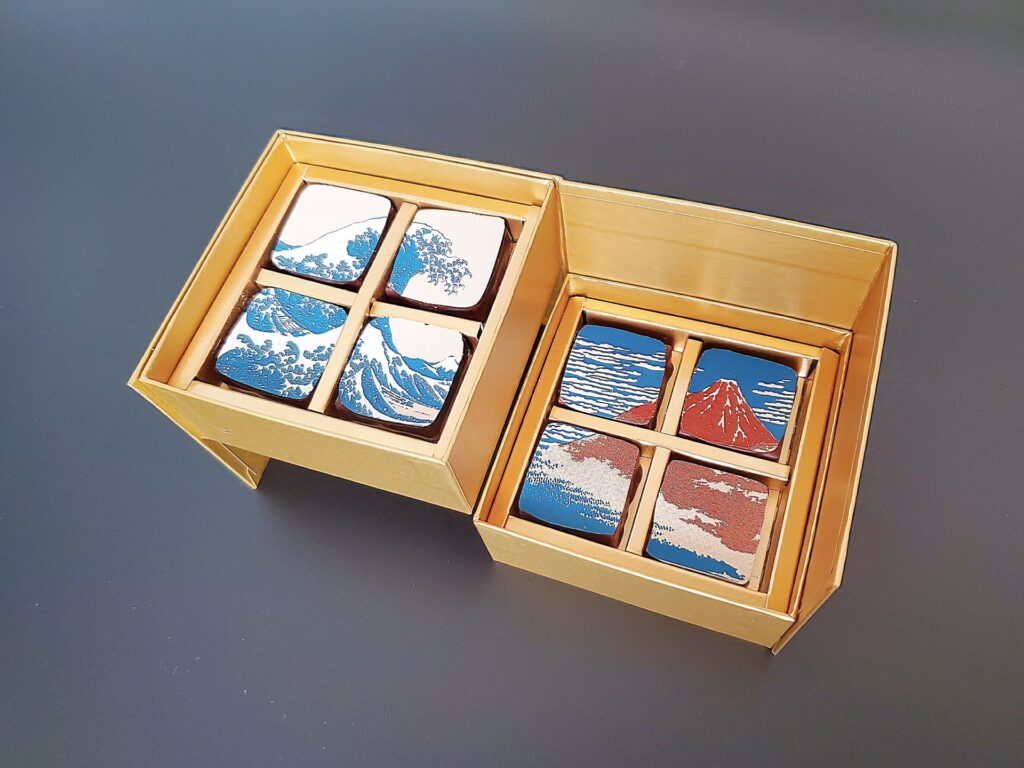

While The Great Wave off Kanagawa remains Hokusai’s most recognizable image, his body of work extends far beyond this iconic print. His series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (1830–1832) captures Japan’s sacred mountain from multiple angles and in changing seasons, revealing both the majesty of nature and the transience of human life. Hokusai also produced Hokusai Manga—fifteen volumes of sketches depicting everything from animals and landscapes to supernatural beings—which served as an encyclopedia of Edo life and an informal textbook for generations of artists.

Later works such as One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji demonstrate his lifelong fascination with the mountain as a symbol of immortality and artistic perfection. Even in his seventies and eighties, Hokusai continued to innovate—experimenting with color gradation, dynamic composition, and delicate linework that prefigured modern graphic design.

His art fused traditional Japanese aesthetics with Western concepts of perspective and shading, giving his prints a three-dimensional dynamism rare in earlier ukiyo-e. This combination of technical mastery and visionary imagination ensured that Hokusai’s influence extended far beyond Japan’s shores.

The Great Wave: Meaning, Composition, and Legacy

The Great Wave off Kanagawa (c. 1831) is perhaps the most famous image in Japanese art—and one of the most recognizable artworks in the world. At first glance, it depicts a towering wave threatening to engulf small boats with Mount Fuji in the background. Yet beneath its striking composition lies a profound meditation on nature’s power and humanity’s fragility.

Hokusai’s use of Prussian blue, a newly imported pigment, and his adoption of linear perspective borrowed from Western art give the print a sense of depth and motion. The wave’s claw-like foam seems almost alive, contrasting the still, eternal mountain beyond. This juxtaposition reflects Buddhist themes of impermanence and the cyclical forces of nature—core ideas that define Hokusai’s worldview.

Globally, The Great Wave inspired generations of artists: Claude Monet studied its perspective, Vincent van Gogh admired its color contrasts, and even contemporary designers continue to reinterpret its form in everything from tattoos to album covers. Its fusion of simplicity and universality embodies what MoMA calls “the birth of global modern art through Japanese vision.”

Hidden Gems: Hokusai’s Lesser-Known Masterpieces

Beyond his famous landscapes, Hokusai’s lesser-known works reveal his versatility and spiritual depth. His Ghost Stories series visualizes Japanese folklore with eerie movement and psychological tension. In his Bird-and-Flower prints, Hokusai’s brushwork becomes meditative—each feather and petal rendered with lyrical precision that anticipates naturalist illustration.

Late in life, he turned increasingly toward religious and moral themes, depicting Buddhist deities, dragons, and mythic creatures as symbols of enlightenment and transformation. The British Museum’s Great Picture Book of Everything—a recently rediscovered collection—showcases hundreds of sketches that explore cosmology, nature, and the human condition with astonishing imagination.

These hidden masterpieces highlight Hokusai’s enduring curiosity and relentless experimentation, qualities that distinguish him as more than a craftsman—he was, above all, a seeker of artistic truth.

Ukiyo-e Printmaking Techniques Explained

Ukiyo-e, the art form Hokusai mastered, was a highly collaborative process that combined design, carving, and printing. The process began with the artist’s sketch (hanshita-e), drawn on thin paper. This design was glued face-down onto a woodblock—typically cherry wood—and meticulously carved by specialists. Multiple blocks were created for each color, requiring extraordinary precision to ensure perfect alignment (registration).

Once carved, the printer applied water-based pigments using brushes, pressing handmade paper onto the inked block with a circular pad called a baren. The result was a luminous, layered print capable of subtle gradations and delicate textures.

Hokusai elevated this process through his inventive compositions and daring use of new pigments and perspective. He proved that ukiyo-e could transcend entertainment to become fine art—an achievement that forever changed the perception of Japanese printmaking.

Tools and Materials in Edo-Era Printmaking

Edo-era printmakers used tools such as hangi-to (carving knives), aisuki (scrapers), and baren (printing pads). Pigments were derived from natural minerals and plants—indigo, safflower, and malachite—though Hokusai’s adoption of imported Prussian blue revolutionized his palette. Handmade washi paper, prized for its strength and absorbency, gave his prints their distinctive softness and clarity.

Every detail—from the wood grain’s texture to the humidity of the printing studio—affected the final outcome, making each print subtly unique.

Collaboration Between Artist, Carver, and Printer

Unlike modern artists who work independently, ukiyo-e production was a team effort. The eshi (artist) designed, the horishi (carver) translated the drawing into wood, and the surishi (printer) brought it to life through careful inking and pressure. Publishers managed distribution and sales.

Hokusai, though only one part of this chain, was the creative engine who envisioned the imagery. His ability to direct collaborators and push technical limits resulted in prints of unprecedented complexity and beauty.

Hokusai’s Influence on Modern and Western Art

Hokusai’s impact on Western art cannot be overstated. In the 19th century, Japanese prints flooded Europe, inspiring the Japonisme movement. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Vincent van Gogh collected Hokusai’s works, adapting his use of asymmetry, color, and flat perspective into Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

Van Gogh openly praised Hokusai’s ability to depict movement and vitality, stating, “He draws waves, and they are alive.” Monet incorporated Hokusai’s framing techniques into his garden designs at Giverny, merging nature and composition in ways that echoed Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Art Nouveau designers, including Alphonse Mucha, borrowed Hokusai’s flowing lines and organic forms.

In Japan, Hokusai’s influence permeates manga and anime—his expressive lines, exaggerated motion, and dynamic framing foreshadowed the modern graphic novel. Contemporary visual storytelling, from Studio Ghibli films to global design brands, still bears traces of his aesthetic DNA.

Hokusai and the Roots of Japanese Pop Culture

Hokusai’s Hokusai Manga volumes, filled with sketches of daily life, mythical creatures, and humor, are widely regarded as precursors to modern manga. His ability to convey emotion and movement through minimal lines laid the foundation for Japan’s later visual narrative culture. The use of exaggerated gestures, “speed lines,” and close-up framing in manga and anime can all trace lineage back to Hokusai’s hand.

Today, Hokusai’s spirit endures in digital art, animation, and even fashion—bridging traditional craftsmanship with contemporary creativity.

Evolution of Style Across Hokusai’s Life

Hokusai’s career can be divided into three main phases.

Early Period (1760–1800): Influenced by the ukiyo-e masters of his time, his works centered on actors and courtesans. His exposure to Western engravings sparked early experiments in perspective.

Middle Period (1800–1830): This was his most productive and innovative era. He produced Hokusai Manga, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, and The Great Wave. His compositions became bold, dynamic, and infused with spiritual symbolism.

Late Period (1830–1849): In his final decades, Hokusai’s art grew increasingly introspective and otherworldly. Works like One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji reveal a quest for artistic immortality. At the age of 88, he declared, “If only Heaven will grant me ten more years… I could become a true artist.”

His stylistic evolution mirrors a lifelong pursuit of perfection—a journey from the worldly to the divine.

Hokusai vs. Hiroshige: A Comparative Look

Utagawa Hiroshige, another master of ukiyo-e landscapes, is often compared with Hokusai. While Hokusai’s art is dramatic, symbolic, and structurally complex, Hiroshige’s prints emphasize atmosphere, emotion, and poetic tranquility.

Hokusai’s waves roar; Hiroshige’s rain whispers. Hokusai sought to depict nature’s power; Hiroshige captured its fleeting beauty. Western audiences initially gravitated toward Hokusai’s bold energy, but both artists profoundly shaped global art movements from Impressionism to contemporary design.

Together, they defined the visual language of Japan for the world.

Where to See Hokusai’s Art Today

Hokusai’s works are preserved in some of the world’s most prestigious institutions.

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York): Extensive ukiyo-e collection including The Great Wave.

- The British Museum (London): Holds rare sketches from The Great Picture Book of Everything.

- MoMA (New York): Features exhibits connecting Hokusai to modern art movements.

- Tokyo National Museum: Houses numerous original prints and drawings.

- Google Arts & Culture: Offers immersive virtual exhibitions and interactive timelines of Hokusai’s life.

For those unable to travel, digital archives allow global audiences to experience Hokusai’s genius in vivid detail—bringing Edo-era craftsmanship into the digital age.

Conclusion: Hokusai’s Enduring Legacy

Katsushika Hokusai remains a symbol of artistic reinvention and timeless creativity. His fusion of traditional Japanese aesthetics with innovative techniques continues to inspire painters, designers, animators, and architects across the world.

From The Great Wave to his quiet sketches of nature, Hokusai captured the essence of existence—beauty, impermanence, and the pursuit of mastery. His art transcends geography and era, bridging the floating world of Edo with the digital landscapes of today.

As modern audiences rediscover his works, Hokusai stands not just as Japan’s most iconic artist, but as a global visionary whose influence flows—like his waves—across centuries.