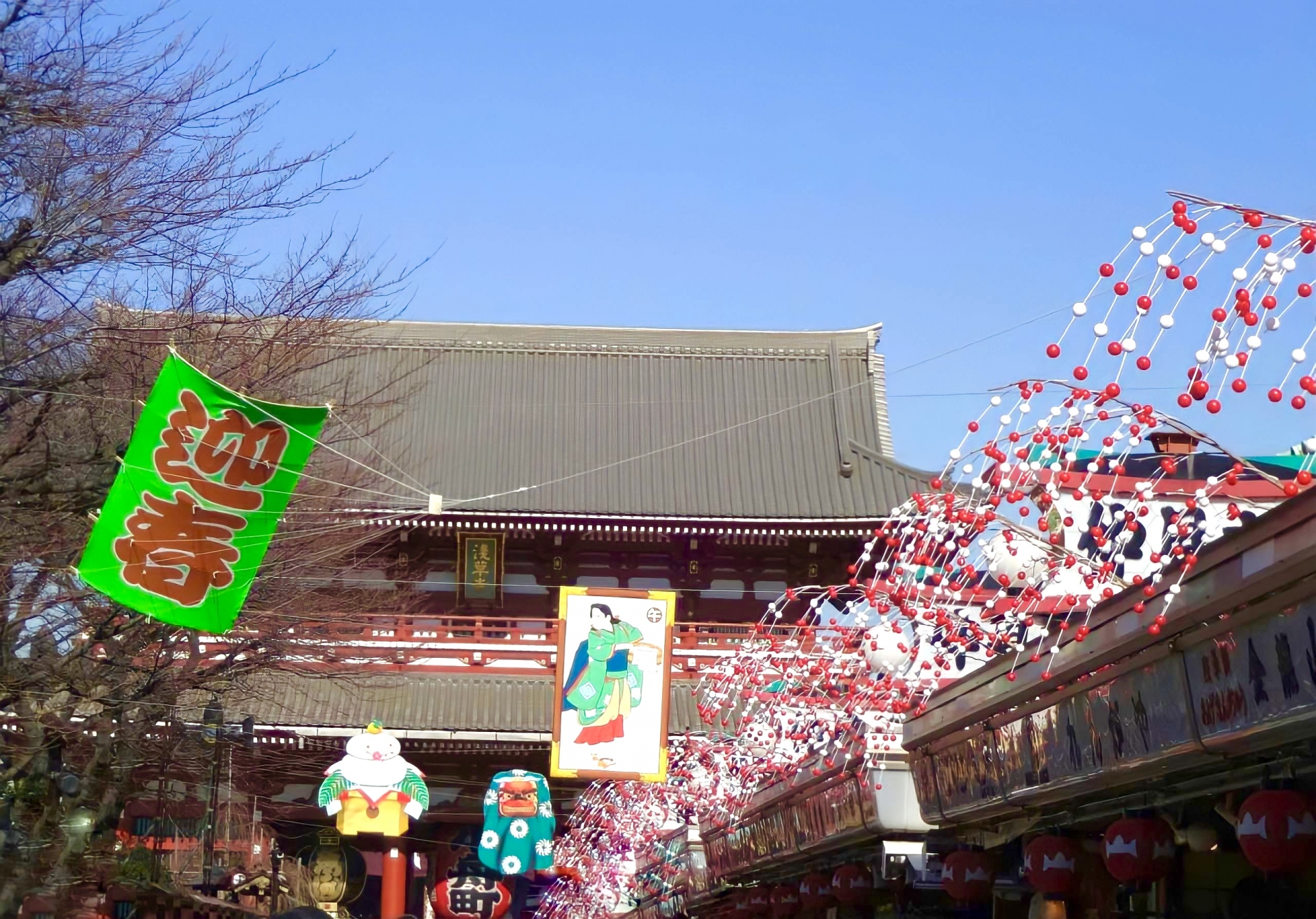

Every New Year in Japan, children eagerly await the moment when grown-ups present small envelopes filled with money — a tradition known as otoshidama. But behind this cheerful custom lies a deep and ancient story. Long before cash-filled envelopes existed, otoshidama originated as a spiritual practice rooted in Shinto beliefs surrounding Toshigami, the deity of the New Year. Families once offered sacred mochi to welcome divine blessings, and the sharing of this blessed mochi became the earliest form of otoshidama. Over centuries, Japan’s social, economic, and cultural landscape transformed, and so did this tradition — from sacred rice cakes to household gifts, and eventually to money. This article traces the evolution of otoshidama and explains why it still matters in modern Japan.

Origins: From Toshigami and Sacred Mochi

The Role of the New Year Deity (Toshigami) and “御歳魂 (Otoshi-dama)”

In ancient Japan, New Year’s Day was dedicated to welcoming Toshigami, a deity believed to descend from the mountains to visit each household. Toshigami brought blessings for the year — prosperity, good harvests, protection, and renewed spiritual vitality. This vitality was often described as a type of “spirit energy” or tama (魂). The term 御歳魂 (otoshi-dama) originally referred not to a tangible item, but to this divine soul gift bestowed upon families.

Early Japanese sources emphasize that the New Year was a moment of spiritual renewal. Families prepared offerings and cleaned their homes to receive Toshigami. The blessings imparted by the deity were believed to be shared among household members, ensuring good fortune for the year ahead. Thus, “otoshidama” began as a sacred concept — a transfer of the deity’s vitality — long before material gifts or money became part of the practice.

Sacred Mochi as the Deity’s Blessing

To welcome Toshigami, families placed kagami mochi — round stacked rice cakes — in their homes as an offering. Mochi was considered a vessel capable of storing spiritual power. After the New Year celebration, the mochi was believed to be filled with Toshigami’s blessings.

The custom of breaking and eating this mochi (known today as kagami biraki) was originally an act of receiving the deity’s strength. Children and family members shared pieces of the sacred mochi, and this blessed food itself was called otoshidama. In other words, otoshidama was once something you ate — a spiritual nourishment passed directly from the deity to the household.

This early stage of otoshidama had nothing to do with money; instead, it symbolized divine protection, renewal, and community unity. Sharing the mochi reaffirmed familial bonds and ensured that everyone began the year with strength and good fortune.

“Year-end Gift”: From Sacred Offering to Family Tradition

As centuries passed, the act of sharing the sacred mochi gradually transformed from a purely religious ritual to a more domestic and familial custom. Families increasingly emphasized the idea of “giving” the mochi to children or younger members as a gesture of goodwill, even when its religious significance gently faded.

The linguistic transformation reflects this shift. The original 御歳魂 (year-spirit blessing) eventually evolved into お年玉, the modern form still used today. This shift marks the beginning of otoshidama as a yearly “gift” — retaining its symbolic meaning of blessing but adapting to an increasingly secular lifestyle.

By this stage, otoshidama had become a cultural rather than strictly spiritual practice: a way to pass on good fortune, show care, and mark the start of a new year. This evolution laid the foundation for the later transition toward material gifts, and eventually, cash.

Historical Evolution: From Mochi and Gifts to Money

Medieval to Edo Period: Gifts to Children and Servants

By the medieval period, the head of a household often distributed token gifts during New Year celebrations to children, servants, and dependents. While mochi remained central, the gifts sometimes included oranges, small goods, or other valuable items.

During the Edo period (1603–1868), merchant families and wealthy households formalized these distributions. They gave small bags containing mochi, dried foods, or symbolic produce such as mandarin oranges — representing prosperity. These gift bags were direct ancestors of today’s decorative pochibukuro envelopes.

Although money was not the norm at this time, the framework of “New Year gift-giving” had already taken shape. Children began to anticipate the annual gifts, and the practice became deeply embedded in Japanese social customs.

Post-Meiji & Showa: Transition to Cash Gifts

The Meiji Restoration (1868) brought rapid modernization, urbanization, and industrialization to Japan. Traditional mochi-making became less common, especially in urban settings. With families moving to cities and living in smaller nuclear households, preparing sacred mochi became impractical.

As cash increasingly dominated the economy, families began giving small amounts of money instead of physical goods or mochi. By the early 20th century, monetary otoshidama was becoming more common in urban areas.

After World War II, during the Showa era (especially the 1950s onward), cash-based otoshidama became the national standard. Decorative envelopes (pochibukuro) became widely available, and children everywhere came to expect money rather than mochi. What began as divine blessings had now firmly become a social custom centered around monetary gifts.

Modern Otoshidama: Customs, Amounts, and Social Meaning

How Otoshidama Is Given Today

Today, otoshidama is almost universally given in pochibukuro, small decorative envelopes featuring cute characters, traditional motifs, or simple patterns. Parents, grandparents, relatives, and sometimes family friends give these envelopes to children.

Practices vary by household: some families give otoshidama only to children of direct relatives, while others extend it to nieces, nephews, or close family friends. The age limit also differs — some stop after high school, others continue through college. The custom remains flexible, adapting to each family’s values and financial situation.

Despite modernization, the core meaning persists: otoshidama is a gesture of goodwill and a blessing for the new year. It is less about material wealth and more about marking a fresh start in a positive way.

Typical Amounts and Trends

While there is no universal rule, common amounts follow age-based expectations:

- Toddlers: ¥1,000–2,000

- Elementary school children: ¥3,000–5,000

- Junior high to high school students: ¥5,000–10,000+

These amounts reflect both cultural norms and practical considerations — older children are more aware of money and may use it for hobbies, savings, or school needs.

Otoshidama also plays a crucial role in children’s financial education. Many parents encourage kids to save a portion of their otoshidama, teaching concepts like budgeting, long-term saving, and responsible spending. Surveys show that many children accumulate significant annual savings solely from otoshidama.

Cultural & Emotional Significance: Hope, Gratitude, and Family Bonds

Although otoshidama involves money, its emotional meaning is far deeper. For children, receiving otoshidama is a joyful highlight of New Year celebrations. For adults, giving otoshidama is an expression of affection, care, and hopes for the child’s growth.

The custom strengthens family relationships across generations, especially during gatherings where relatives meet only once or twice a year. The act of receiving and expressing gratitude also reflects traditional Japanese values — respect, humility, and intergenerational connection.

Thus, otoshidama remains a symbolic gift of blessing and hope, not simply a financial transaction.

Why Otoshidama Still Matters: Continuity & Change

Continuity: A Link to Ancient Traditions

Despite evolving forms, otoshidama retains a direct connection to its ancient origins. Just as sacred mochi once carried Toshigami’s blessings, today’s envelopes symbolically pass on good fortune from adults to children. The essential meaning — sharing blessings for the coming year — remains unchanged.

This continuity helps preserve cultural memory. Even as modern families celebrate New Year differently from their ancestors, otoshidama maintains a bridge to Japan’s spiritual heritage and its ritual of welcoming renewal each year.

Change: Urbanization, Economy & Modern Lifestyles

The shift from mochi to money reflects broader social change: the decline of agricultural households, the rise of city life, and the growing influence of cash economies. Nuclear families have fewer opportunities to make traditional foods, and children’s desires increasingly align with modern consumer culture.

Along with these changes come new pressures. Parents feel expectations to give higher amounts, and children spend money in more diverse ways — from technology to online subscriptions. Still, most families find ways to balance tradition with practicality, ensuring that the meaning of otoshidama is preserved.

Additional Perspectives & What’s Changing

Regional and Generational Differences (Under-covered Topic)

Otoshidama practices differ subtly across Japan. In Eastern Japan, amounts tend to be standardized, reflecting urban lifestyles and fixed expectations. In Western Japan, traditions are sometimes more flexible, with greater emphasis on symbolic gifts or varying amounts depending on family ties. Rural regions may give more modest amounts or extend the custom across broader family networks.

Generational differences are also notable. Older generations often recall receiving small amounts or non-monetary gifts, while younger parents today navigate higher economic expectations. Some families debate when to stop giving otoshidama — after high school, at coming-of-age age (20), or upon entering the workforce. These variations highlight the adaptability of the custom and reveal how Japanese culture evolves with social realities.

Future of Otoshidama: Digital Gifts, Financial Education, and Evolving Norms

In recent years, digital options have begun reshaping otoshidama. Prepaid cards, e-money, and cashless payment services are increasingly popular, especially among teenagers who use smartphones daily. While older generations may prefer cash, parents working in modern tech-driven environments often see digital otoshidama as practical and secure.

Beyond the format, otoshidama’s role in financial education is growing. Teachers and financial planners encourage parents to use otoshidama as a teaching opportunity, guiding children to set savings goals, understand interest, and build responsible spending habits. In a cashless society, these lessons become even more vital.

As society continues to change, otoshidama will likely evolve — perhaps integrating digital platforms while maintaining traditional envelopes for ceremonial meaning.

Conclusion: Why Otoshidama Endures

The story of otoshidama spans centuries: from sacred mochi offered to Toshigami, to household gifts of rice cakes, to modern cash-filled envelopes. Although the form has transformed, the heart of the tradition remains unchanged — sharing blessings, fostering family bonds, and celebrating renewal at the start of each year.

Otoshidama endures because it represents hope. Whether in the form of sacred mochi or digital money, it symbolizes the desire to pass on strength and good fortune to the next generation. As Japan continues to modernize, otoshidama will adapt, but its spiritual heart — the idea of giving blessings — will remain a cherished part of New Year celebrations.