Hatsumode, the first shrine or temple visit of the New Year, stands as one of Japan’s most recognizable and widely practiced traditions. While modern Hatsumode appears as a festive cultural event filled with crowds, sacred rituals, and good-luck charms, its origins reach deep into Japan’s premodern religious landscape. What began as overnight shrine-staying rites eventually transformed into a nationwide custom observed by millions every January.

This article traces the evolution of Hatsumode—from ancient beliefs like toshigomori and Edo-period ehō-mairi to the modernization of the Meiji era—and explores why the tradition continues to serve as a meaningful spiritual and cultural anchor in Japan today.

Early Origins: From Toshigomori to the First Shrine Rituals

The earliest roots of Hatsumode can be traced to toshigomori, an ancient ritual in which the head of a household spent New Year’s Eve inside a local shrine. Records indicate that this practice dates back as early as the Heian period, when the family patriarch stayed overnight to welcome the Toshigami, the deity who brought agricultural abundance and protection for the coming year. By remaining at the shrine through the night, he symbolically represented the entire household in receiving the New Year deity’s blessings.

Toshigomori was closely tied to agricultural rhythms. Communities relied on the Toshigami’s favor for stable weather, good harvests, and protection from illness. The ritual reinforced the bond between local families and their ancestral deities at a moment of great spiritual significance—the transition from one year to the next.

As daily life evolved and travel between communities became more common, the tradition of overnight shrine stays gradually faded. By the medieval and early Edo periods, the idea of welcoming the New Year through shrine visitation expanded beyond the household head, with families and community members making shorter visits rather than staying overnight. This shift marked an important step toward the more open, accessible form of New Year shrine visits that would eventually become modern Hatsumode.

The Emergence of Ehō-mairi: Directional Worship in the Edo Period

During the Edo period, the practice of ehō-mairi—visiting a shrine or temple located in the year’s auspicious direction—became widely popular. Rooted in onmyōdō (yin-yang cosmology) and folk belief, the “lucky direction” changed annually.

Importantly, ehō-mairi was traditionally performed around the lunar New Year (kyūshōgatsu), not the modern January 1.

Because the start of the year followed the old lunar calendar, people undertook their directional visit as part of their New Year’s rites according to the timing of the old New Year festival.

As urban mobility increased and road networks improved during the Edo era, ordinary townspeople, merchants, and artisans began traveling beyond their local shrines to seek out auspicious temples and shrines located in the designated direction. The custom combined travel, popular superstition, and seasonal celebration in ways that broadened the scope of New Year observances.

By encouraging people to visit shrines beyond their ujigami (local tutelary deity), ehō-mairi laid essential groundwork for the modern phenomenon of traveling across cities—or even prefectures—to conduct Hatsumode at major spiritual centers.

Modernization and Formalization: Hatsumode from Meiji to the 20th Century

The modern form of Hatsumode took shape during the Meiji and Taishō periods, when Japan underwent rapid industrialization and social reorganization. As railway networks expanded, travel to famous shrines became accessible to the general public. Major sites such as Meiji Shrine in Tokyo and Sumiyoshi Taisha in Osaka emerged as central New Year destinations in rapidly growing cities.

It was during the late Meiji to Taishō eras that the term Hatsumode came into widespread use. As Japan shifted to the Gregorian calendar and modernized its institutions, shrine visits transitioned from overnight New Year’s Eve vigils to the familiar pattern of visiting between January 1 and 3. State Shinto policies also contributed to standardizing rituals and promoting shrine visits as part of national holiday practices.

By the early 20th century, Hatsumode had become firmly established as both a spiritual act and a modern social ritual. Railway companies promoted New Year travel through special campaigns, helping cement the now-common experience of visiting major shrines alongside millions of fellow worshippers.

Cultural and Spiritual Meaning: Purification and New Beginnings

Despite its modernization, Hatsumode remains deeply symbolic. Many people visit shrines to purify themselves of past misfortunes, express gratitude for blessings received, and pray for happiness, health, and prosperity in the new year. The concept of harai—ritual purification—resonates strongly at the start of the year, offering a sense of renewal and emotional reset.

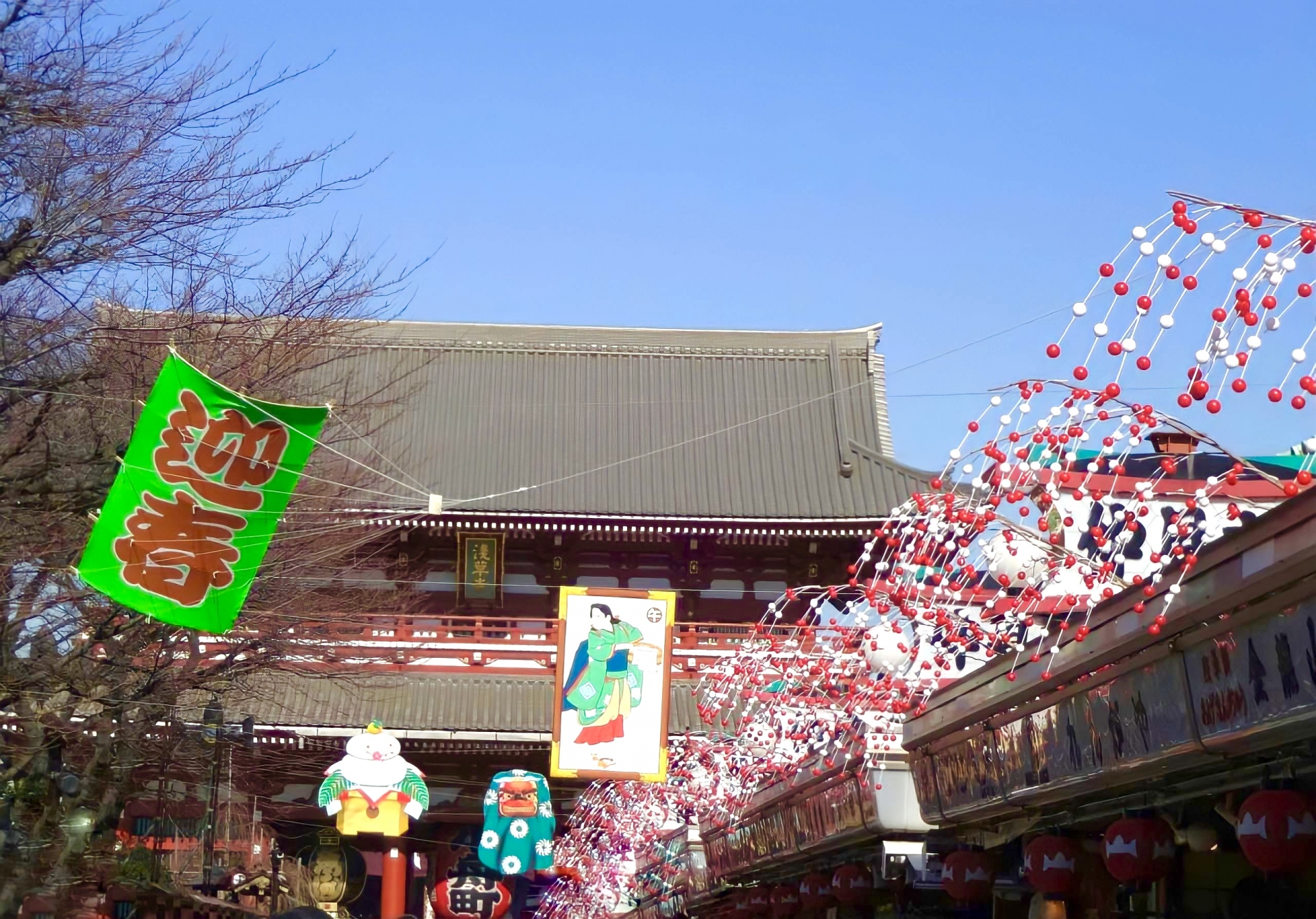

Hatsumode also reflects Japan’s rich tradition of Shinto-Buddhist coexistence. While shrines are the most common destinations, people often visit temples as well—to ring the bell, purchase charms, or draw omikuji fortune slips. This syncretism highlights the flexible and inclusive nature of Japanese spirituality.

Socially, Hatsumode reinforces family and community bonds. Families visit shrines together, enjoy sweet amazake, and browse festive food stalls. In this way, Hatsumode functions as both a sacred practice and a cherished cultural event marking the beginning of the year.

How Hatsumode Is Practiced Today: Customs, Crowds & Popular Shrines

Most people conduct Hatsumode between January 1 and 3, though visits often continue through matsu-no-uchi, the first week to ten days of the new year. Some begin their observance on New Year’s Eve by participating in joya-no-kane, the ringing of Buddhist temple bells at midnight, followed by a shrine visit immediately afterward.

Common practices during Hatsumode include:

- Purification: rinsing hands and mouth at the chozuya

- Prayer etiquette: two bows, two claps, one bow

- Monetary offerings: tossing coins into the offering box

- Omikuji: drawing fortunes, often tied to designated racks

- Omamori: purchasing charms for health, safety, or success

- Returning old talismans: disposing of the previous year’s charms at the shrine

Major shrines attract enormous crowds. For example:

| Shrine | Location | Estimated New Year Visitors |

| Meiji Shrine | Tokyo | Over 3 million |

| Naritasan Shinshoji | Chiba | Around 3 million |

| Fushimi Inari Taisha | Kyoto | Millions annually |

| Sumiyoshi Taisha | Osaka | Over 2 million |

While many still take part in the January 1–3 rush, early or late visits have grown more common—particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic—allowing participants to avoid heavy crowds.

Why Hatsumode Continues Today: Social, Cultural & Emotional Value

Hatsumode remains popular because it offers a meaningful “reset” for the year. Even those who do not identify as religious find comfort in beginning the year with a symbolic act of purification, reflection, and hope.

Its flexibility also contributes to its endurance. Some people visit at dawn on January 1, others go during the first week of January, and many stop by a local shrine or temple on their commute. This adaptability allows Hatsumode to persist across generations and lifestyles.

Modern variations include avoiding crowded periods, incorporating Hatsumode into domestic travel plans, or experiencing it as a foreign resident. Compared with Western countdown parties or Korean ancestral rites, Hatsumode stands out for its blend of spiritual intention, wish-making, and festive public atmosphere—ensuring its role as a cherished New Year tradition.

Broader Perspectives on Hatsumode: Regions, Generations, and Economy

Although Hatsumode is practiced nationwide, regional differences are notable. In the Kanto region, urban residents often visit large shrines such as Meiji Shrine or Kawasaki Daishi, while Kansai residents may head to places like Fushimi Inari Taisha or Kiyomizudera. Rural communities tend to maintain stronger ties with their ujigami shrines, preserving local traditions.

Generational patterns also vary. Younger people may view Hatsumode more as a cultural outing or social event, whereas older generations emphasize traditional prayers, protective charms, and gratitude rituals.

Transportation and tourism have further shaped modern Hatsumode. Train stations extend service hours, and travel agencies promote New Year shrine tours. The economic impact is significant: revenue from charms and fortune slips supports shrines, while local markets and vendors benefit from increased foot traffic. Hatsumode thus serves not only as a cultural ritual but also as a seasonal economic driver.

Conclusion: Hatsumode as a Living New Year Tradition

Hatsumode has evolved from ancient toshigomori rites dating back to the Heian period and Edo-period ehō-mairi visits held around the lunar New Year into a modern tradition practiced by millions. Its development reflects broader changes in transportation, religion, and daily life, yet its core purpose—purification, gratitude, and hope—remains unchanged.

Whether experienced as a midnight shrine visit, a peaceful family outing, or a quiet trip later in January, Hatsumode continues to embody Japan’s spirit of renewal. For travelers visiting Japan during the New Year season, participating in Hatsumode offers a memorable opportunity to connect with centuries of culture, spirituality, and community tradition.