Hyakunin Isshu—often translated as “One Hundred Poets, One Poem Each”—is Japan’s most famous classical poetry anthology. Compiled in the 13th century and still memorized today through traditional card games, it offers an unexpectedly approachable gateway into Japanese aesthetics: seasons, love, longing, travel, and impermanence.

This guide explains the essentials of Hyakunin Isshu in plain English, introduces famous poems and popular ways to play, and shows how you can experience it through learning, games, and travel in Japan.

Hyakunin Isshu in One Minute (Quick Summary)

Hyakunin Isshu is a curated collection of 100 waka (tanka) poems, each written by a different poet. When people refer to Hyakunin Isshu today, they are almost always referring to the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu, compiled in the early 13th century by Fujiwara no Teika.

Its importance lies in several overlapping roles. Literarily, it offers a compact overview of Japanese poetry from the 7th to the 13th century. Culturally, it preserves key Japanese aesthetic ideas such as seasonal awareness and mono no aware—the sensitivity to impermanence. Practically, it serves as the textual foundation of karuta, one of Japan’s most iconic traditional games.

What Is Hyakunin Isshu? (Meaning, Origin, and the “Ogura” Version)

The term Hyakunin Isshu literally means “one hundred people, one poem.” While other anthologies follow a similar concept, the name today almost exclusively refers to the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. This version was compiled during the Kamakura period and draws together poems written over several centuries, from early imperial court poetry to medieval works.

Teika’s achievement was not simply collecting famous poems, but arranging them with remarkable balance. Different eras, poetic voices, emotional tones, and social backgrounds are carefully interwoven. Because of this editorial clarity, his selection became standardized, memorized, and widely transmitted. For beginners, this means that Hyakunin Isshu is not a vague category of texts, but a single, stable anthology with a shared cultural reference point.

Who Was Fujiwara no Teika?

Fujiwara no Teika was one of the most influential figures in Japanese literary history. A poet, critic, and editor, he lived during a transitional period when classical court culture was giving way to medieval Japan. His aesthetic ideals—clarity of emotion, restraint, and refined imagery—shaped not only Hyakunin Isshu but the broader understanding of what “classical Japanese poetry” should be.

Much like a canon-forming editor in Western literature, Teika’s selections determined which poems were preserved, memorized, and taught for generations. Understanding his role helps readers see Hyakunin Isshu as a deliberately crafted literary snapshot rather than a random assortment of verses.

Waka / Tanka Basics: How These Poems Work

All poems in Hyakunin Isshu are waka, also known as tanka, composed in a fixed 5–7–5–7–7 syllable pattern. Rather than telling extended stories, waka capture a single emotional moment, often anchored in nature or seasonal imagery.

Haiku, which many English readers are more familiar with, developed later and follows a shorter 5–7–5 structure. While haiku emphasize immediacy and minimalism, waka allow for emotional turns and reflection, especially in their final lines. As a result, waka often feel closer to short lyric poems, making them surprisingly accessible to modern readers.

Key Themes You’ll See Again and Again

Despite spanning centuries, the poems of Hyakunin Isshu return repeatedly to a small set of themes. Seasonal imagery—cherry blossoms, autumn leaves, moonlight, snow—serves as more than decoration; it reflects inner emotional states. Love poems often focus on waiting, separation, or unspoken feelings rather than fulfillment. Travel poems emphasize uncertainty and distance, while many verses express mono no aware, the quiet sadness that comes from knowing beauty will fade.

A common poetic movement begins with an external scene and ends with a personal realization. Symbols such as “wet sleeves” frequently imply tears, as sleeves were thought to absorb emotion. Recognizing these conventions allows beginners to appreciate the poems without deep knowledge of classical Japanese.

Famous Poems from Hyakunin Isshu (Beginner Favorites)

While all 100 poems are valued, a few are especially approachable for first-time readers.

Poems by Ariwara no Narihira use vivid natural imagery—such as autumn leaves flowing down a river—to mirror lingering memories of love. Ono no Komachi is known for poems reflecting on fading beauty and the passage of time, themes that resonate strongly with modern readers. In contrast, Semimaru writes about chance meetings and partings along life’s journey, capturing the poignancy of fleeting encounters.

Rather than attempting to memorize everything, beginners benefit most from starting with one or two poems that emotionally resonate. Personal connection matters more than completeness.

Why Hyakunin Isshu Is Still Famous: Karuta and New Year Traditions

Hyakunin Isshu remains culturally vibrant largely because of its connection to karuta, a traditional card game commonly played during New Year celebrations. In karuta, poetry becomes interactive and social rather than purely academic.

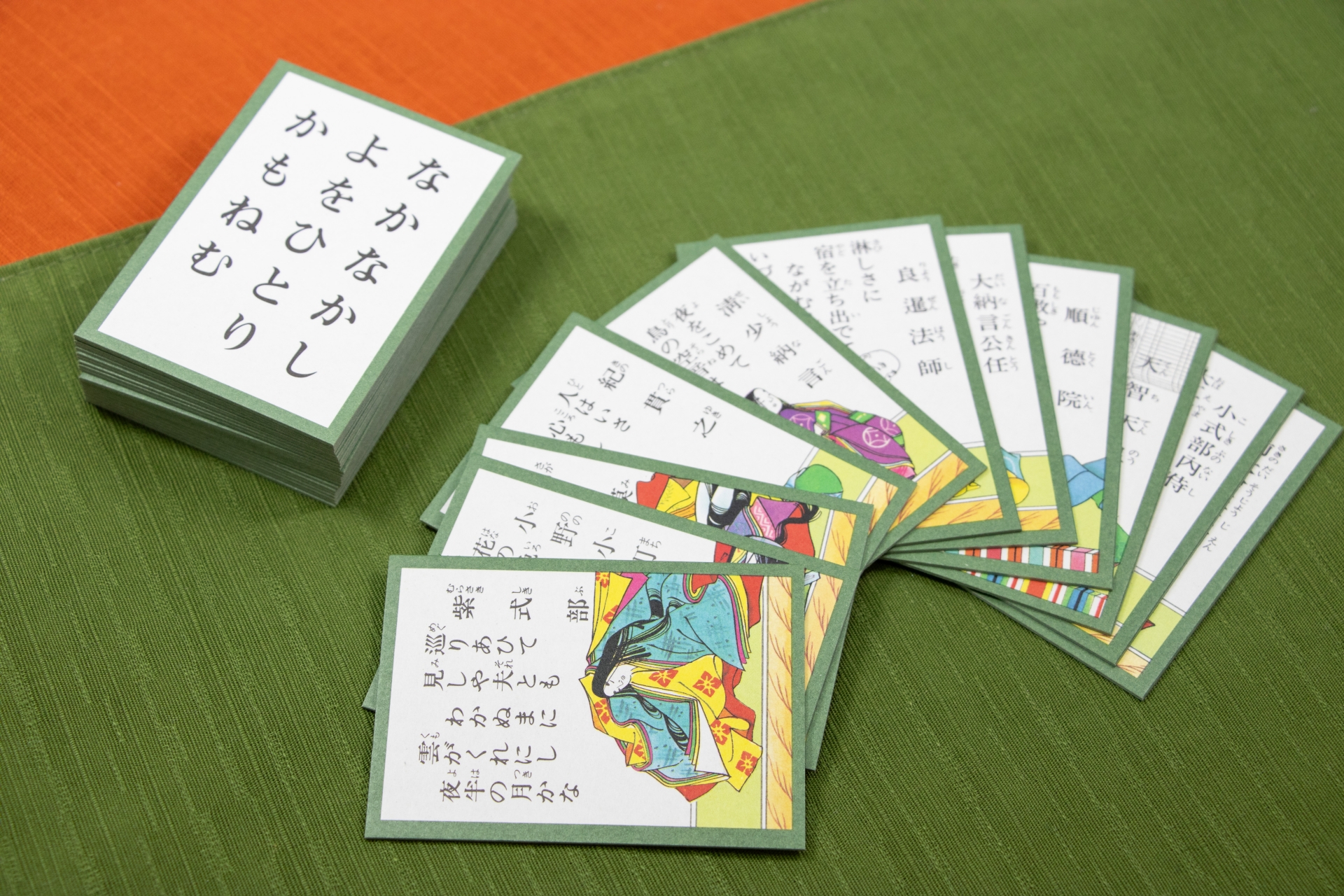

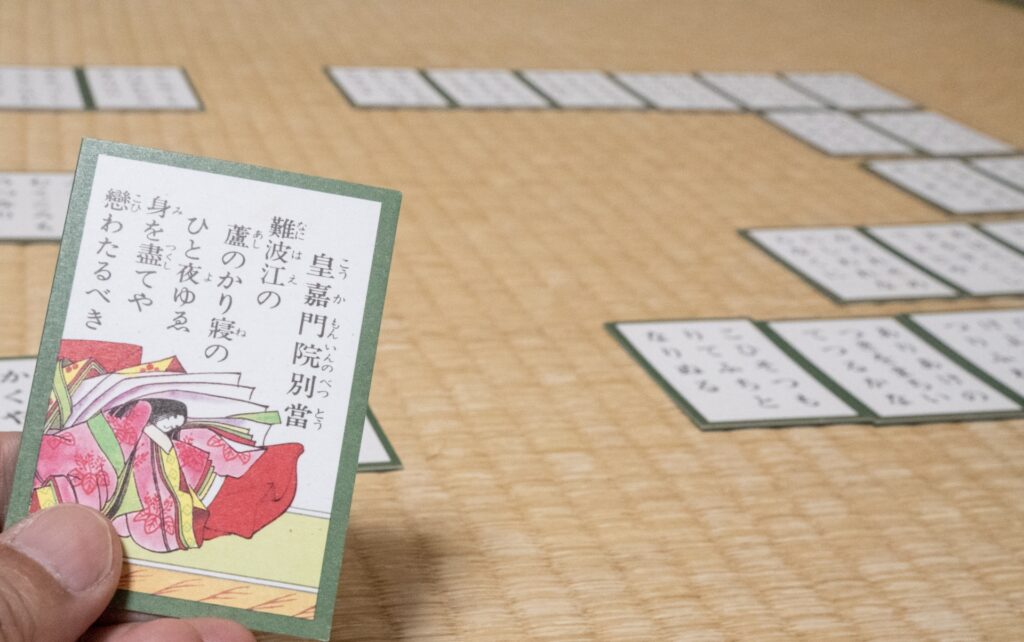

One set of cards (yomifuda) contains the full poem and is read aloud, while another set (torifuda) contains only the second half. As the reader recites a poem, players listen closely and race to grab the matching card. Through repetition, listening, and play, participants internalize classical poetry almost unconsciously.

How to Play Hyakunin Isshu: Popular Styles

Not all karuta is competitive. Traditional family-style games make Hyakunin Isshu accessible to all ages.

Chirashi-dori (scatter matching) is the most common style. Cards are spread out, and players take the correct one as it is read. It works well for families, classrooms, and casual gatherings, allowing beginners to learn gradually.

Bozu mekuri relies on illustrated cards rather than poem recognition. Because outcomes depend largely on chance, even young children can participate. It is often used as a first step, helping players become familiar with the visual world of Hyakunin Isshu before moving on to poetry-based play.

Competitive Karuta in Plain English: What Is “Kimariji”?

Competitive karuta transforms Hyakunin Isshu into a fast-paced, two-player mind sport. The key concept is kimariji, the syllable at which a poem becomes uniquely identifiable among all 100 poems.

Rather than memorizing entire poems at first, players learn where recognition becomes possible. Success depends on precision in listening and anticipation, not just speed. This balance of memory, concentration, and physical reflex is why competitive karuta is often described as both a sport and a mental discipline.

How to Start Reading Hyakunin Isshu (Without Getting Overwhelmed)

There is no single correct way to begin. Some readers prefer approaching the poems by theme—love, seasons, or travel—while others read one poem a day to build familiarity slowly. Many people find that learning through karuta makes the poems feel more natural and less intimidating.

When choosing translations, annotated editions are often the most beginner-friendly, as they explain cultural references and imagery. Poetic translations emphasize emotional flow, while literal ones prioritize accuracy. The best choice depends on whether your goal is study, enjoyment, or both.

Experience Hyakunin Isshu in Japan

The “Ogura” in Ogura Hyakunin Isshu refers to the Kyoto area near Mount Ogura, where poetry, landscape, and seasons intersect. Travelers can experience Hyakunin Isshu beyond books through museums, cultural exhibits, and seasonal scenery that echoes famous poems.

For visitors, Hyakunin Isshu offers an ideal half-day cultural experience—connecting literature, history, and place in a way that feels tangible rather than academic.

Conclusion: Hyakunin Isshu as a Gateway to Japanese Culture

Hyakunin Isshu is more than a classical poetry collection. It can be read as literature, played as a game, and experienced through travel. You do not need to memorize all 100 poems to appreciate it. Understanding a few verses, enjoying a simple karuta game, or visiting a related place in Kyoto is enough to begin.

In that sense, Hyakunin Isshu remains one of the most accessible and rewarding entry points into Japanese culture—bridging centuries of poetry with everyday enjoyment today.