Otoshidama (お年玉) is one of Japan’s most cherished New Year traditions, in which children receive money from adult relatives as a symbol of blessing for the year ahead. Originally rooted in ancient beliefs surrounding Toshigami, the New Year deity, and offerings of rice, Otoshidama has evolved into a modern custom involving colorful envelopes known as pochibukuro.

This article provides a complete guide to Otoshidama, exploring its origins, cultural meaning, modern practices, etiquette, and how it relates to similar traditions across the world.

What Is Otoshidama? (Definition and Overview)

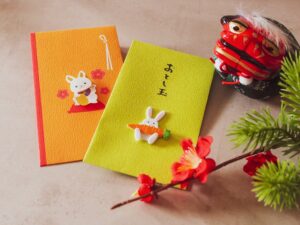

Otoshidama (お年玉) is a cherished Japanese New Year tradition in which children receive small amounts of money from their parents, grandparents, and relatives. It is usually given between January 1st and 3rd, during Japan’s New Year celebrations known as Shōgatsu (正月). The gift symbolizes a blessing for good fortune, health, and growth in the year to come.

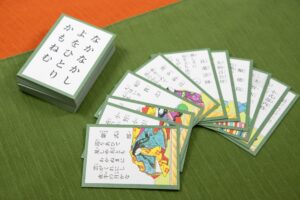

Money for Otoshidama is typically placed inside a small, beautifully designed envelope called a pochibukuro (ポチ袋). These envelopes often feature cute or auspicious designs—such as rabbits, dragons, Mount Fuji, or traditional patterns symbolizing luck. Children eagerly await these envelopes, often comparing the designs and guessing how much might be inside. For many, Otoshidama is the highlight of the New Year—a moment of excitement and familial connection that transcends generations.

While the custom centers on children, the spirit of Otoshidama reflects gratitude, family bonding, and the passing of blessings from one generation to the next. In some workplaces, adults may even exchange small “Otoshidama-style” gifts as tokens of appreciation and good luck.

The History and Origins of Otoshidama

The roots of Otoshidama stretch back to Japan’s ancient Shinto traditions and the veneration of Toshigami (年神)—the New Year deity believed to visit each household to bestow prosperity and blessings. Historically, people offered mochi (rice cakes) to Toshigami as a sacred food representing life and fertility. This divine offering, known as toshidama, symbolized receiving part of the god’s spirit for the coming year.

Over time, as society evolved—particularly during the Muromachi and Edo periods—this spiritual exchange transformed into a material one. Instead of offering or sharing rice cakes, families began gifting coins, and later bills, to symbolize prosperity. The meaning of Otoshidama thus shifted from divine offering to a human gesture of goodwill and blessing.

Toshigami and New Year Beliefs

Toshigami is a Shinto deity associated with the New Year, harvest, and family prosperity. According to belief, Toshigami descends from the mountains each New Year’s Eve to visit households and bring blessings. Offerings of rice and kagami mochi were made to welcome and honor the deity. Rice, being the foundation of life in Japan, symbolized strength and renewal.

The original “Otoshidama” referred not to money, but to the rice or mochi distributed among family members after the Toshigami rituals. Each portion carried spiritual significance—sharing the deity’s life force and ensuring well-being for the year ahead. The transition from spiritual rice offerings to monetary gifts reflects how traditional values adapted alongside societal changes.

From Rice Cakes to Money — Cultural Evolution

By the Edo period, Japan’s economy had grown, and currency became a daily reality for ordinary people. Gift-giving customs evolved accordingly. Wealthy families and merchants began giving small coins instead of rice cakes as symbolic offerings to children or apprentices. This adaptation merged practicality with spiritual tradition—retaining the intent of blessing while aligning with an increasingly monetized society.

Modern Otoshidama retains that balance: it honors ancient beliefs while fitting seamlessly into contemporary life. The envelope, once a vessel for sacred rice, now carries money but remains a symbol of care, fortune, and renewal.

Otoshidama Today: Customs and Practices

In modern Japan, Otoshidama is an essential part of New Year celebrations. It is typically given between January 1st and 3rd, during family gatherings or visits to relatives’ homes. Parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles usually give money to children up to high school or university age.

The envelopes—pochibukuro—are as central as the money itself. Families often choose envelopes with designs that reflect the zodiac animal of the year or motifs of good luck such as cranes, pine trees, or daruma dolls. Some parents even personalize them with hand-written notes or stickers.

Every family has its own variation of the custom. Some give a single envelope per child; others might pool Otoshidama funds into a collective family pot for saving or charity. While the amounts and styles vary, the sentiment remains constant: a heartfelt wish for a happy and prosperous year.

Typical Amounts and Age Guidelines

The amount of money given as Otoshidama depends on the child’s age, family relationship, and financial circumstances. While there are no strict rules, general guidelines are often followed.

Preschool children typically receive smaller amounts, while elementary and junior high school students receive gradually higher sums. High school and university students may receive larger amounts, though this varies greatly by household. Regional customs and family values play a major role, and what matters most is the intention behind the gift rather than the exact amount.

Digital and Modern Variations

In recent years, Japan’s cashless movement has influenced even this age-old tradition. Digital versions of Otoshidama—using e-money, QR code transfers, or digital gift cards—have become more popular, especially among tech-savvy families. Some payment apps even offer seasonal Otoshidama-style designs.

Despite this modernization, many families still prefer physical envelopes for younger children, as they convey warmth, ceremony, and excitement. These digital trends show that while the form may change, the essence of Otoshidama remains intact.

Etiquette and Manners for Otoshidama

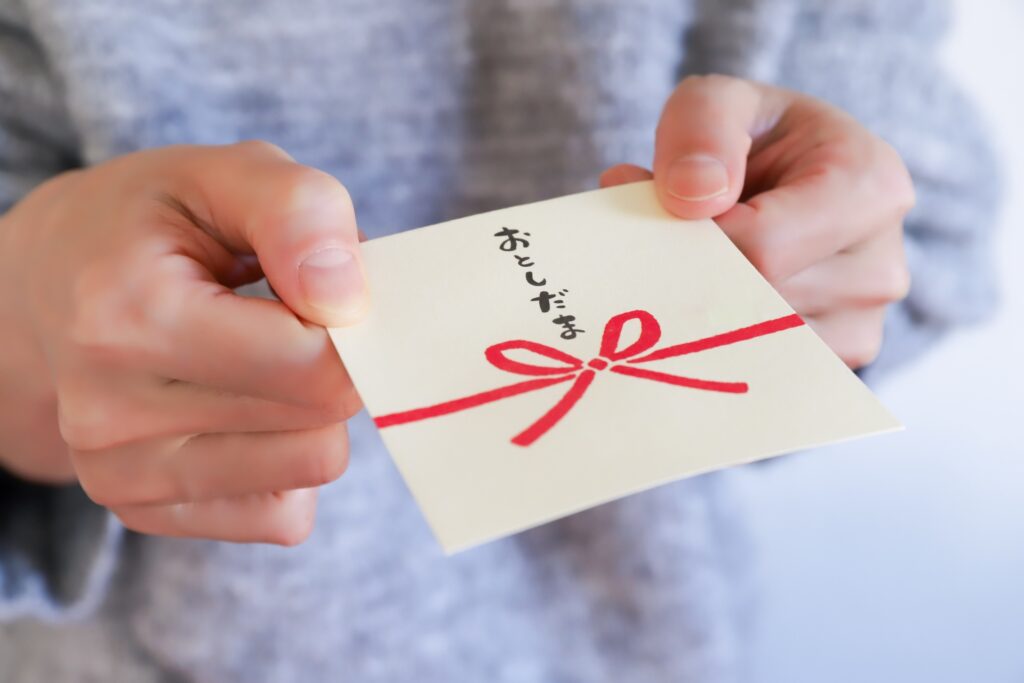

Giving and receiving Otoshidama comes with certain cultural manners. Bills should be new and neatly folded before being placed inside the envelope. It is polite to hand the pochibukuro with both hands while offering New Year greetings.

Children are expected to receive the envelope politely and express thanks before putting it away. Opening it immediately may be considered impolite, though close family settings are often more relaxed.

For adults, moderation is important. Giving excessively large amounts can create pressure or imbalance among siblings and relatives. Otoshidama is meant to be a thoughtful blessing, not a competition.

Otoshidama vs. Similar Traditions Around the World

Otoshidama shares similarities with customs such as Chinese hongbao and Korean sebaetdon. All involve gifting money to symbolize good fortune and blessings for the new year. However, Otoshidama is unique in its strong connection to Shinto beliefs and the Toshigami deity.

Timing, recipients, envelope design, and cultural meaning differ across countries. These variations highlight how similar ideas—welcoming a new year with generosity—are expressed differently across cultures.

Tips for Families and Visitors

For international residents or travelers in Japan, participating in Otoshidama can be a meaningful cultural experience. Modest amounts are perfectly acceptable, and choosing a simple pochibukuro from a local store is enough to show respect.

Offering the gift during New Year greetings with a polite phrase is appreciated. More than anything, sincerity and respect for the tradition matter more than following strict rules.

Conclusion: Why Otoshidama Still Matters Today

Otoshidama continues to be a powerful symbol of renewal, generosity, and family connection in modern Japan. For children, it represents excitement and independence; for adults, it is a way to pass on blessings and values to the next generation.

Even as payment methods change and lifestyles evolve, the spirit of Otoshidama remains the same. It is a tradition that celebrates new beginnings and the enduring importance of human connection.