Each New Year in Japan (Oshōgatsu) isn’t just a time for quiet reflection, shrine visits, or enjoying traditional osechi cuisine. It is also a season filled with laughter, friendly competition, and family bonding through traditional games. For generations, families have welcomed the New Year with activities such as fast-paced karuta, the graceful paddle game hanetsuki, the humorous face-building challenge of fukuwarai, and children’s favorites like kite flying and spinning tops.

In this comprehensive guide, you’ll discover the origins, rules, cultural symbolism, and modern-day enjoyment of these beloved Japanese New Year games—ideal for travelers, educators, families, and anyone curious about Japanese tradition.

The Heart of Japanese New Year Games

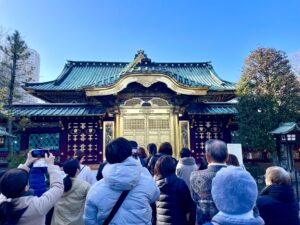

Japanese New Year celebrations are rooted in themes of rebirth, good fortune, and purification. Historically, the holiday served as a spiritual reset—inviting positive energy into the home while driving misfortune away. Games naturally became part of this custom because they foster joy, unity, and hope, qualities believed to influence the year ahead.

Unlike everyday games, New Year games were traditionally associated with auspicious beginnings. A well-performed game or shared laughter could be interpreted as a good omen. Since Oshōgatsu is also one of the rare moments when extended families gather, these group-friendly games became an essential part of seasonal bonding.

From children mastering koma spinning tops to adults enjoying classical poetry through karuta, New Year games serve as cultural bridges—preserving tradition and strengthening family ties across generations.

The Evolution of Japanese New Year Games Through History

Japanese New Year games evolved over many centuries, shaped by court culture, urban society, and print media.

Heian Period (794–1185)

The origins of several games can be traced to aristocratic pastimes. A key example is kai-awase (shell matching game)—a luxurious game in which noblewomen matched pairs of decorated clam shells. This elegant matching activity is widely regarded as an early precursor to karuta, since it shares the concept of identifying and pairing corresponding pieces.

Decorated kites and poetic contests also flourished during this era, laying cultural groundwork for later New Year games.

Edo Period (1603–1868)

This era solidified most of today’s well-known New Year amusements.

- Kite flying became a nationwide craze.

- Karuta evolved into its Hyakunin-Isshu form.

- Hanetsuki became popular among young girls, connected with spiritual beliefs about protection.

Commoner households embraced these activities as urban culture blossomed.

Meiji to Early 20th Century

Mass printing gave rise to sugoroku, simple board games distributed as magazine or newspaper extras during the New Year season. This period spread many local variations across Japan.

Modern Day

While some games declined due to urbanization, safety regulations, or lack of space, others have transformed into decorative traditions or seasonal events. For example, hagoita paddles are now cherished New Year ornaments displayed in homes and temple fairs.

Overall, New Year games evolved from aristocratic amusements to everyday cultural icons, carrying both entertainment and symbolic meaning.

Major Traditional New Year Games

Below are the most iconic New Year games still loved across Japan. Each blends history, symbolism, and straightforward fun suitable for all ages.

Karuta (歌ガルタ / Hyakunin-Isshu)

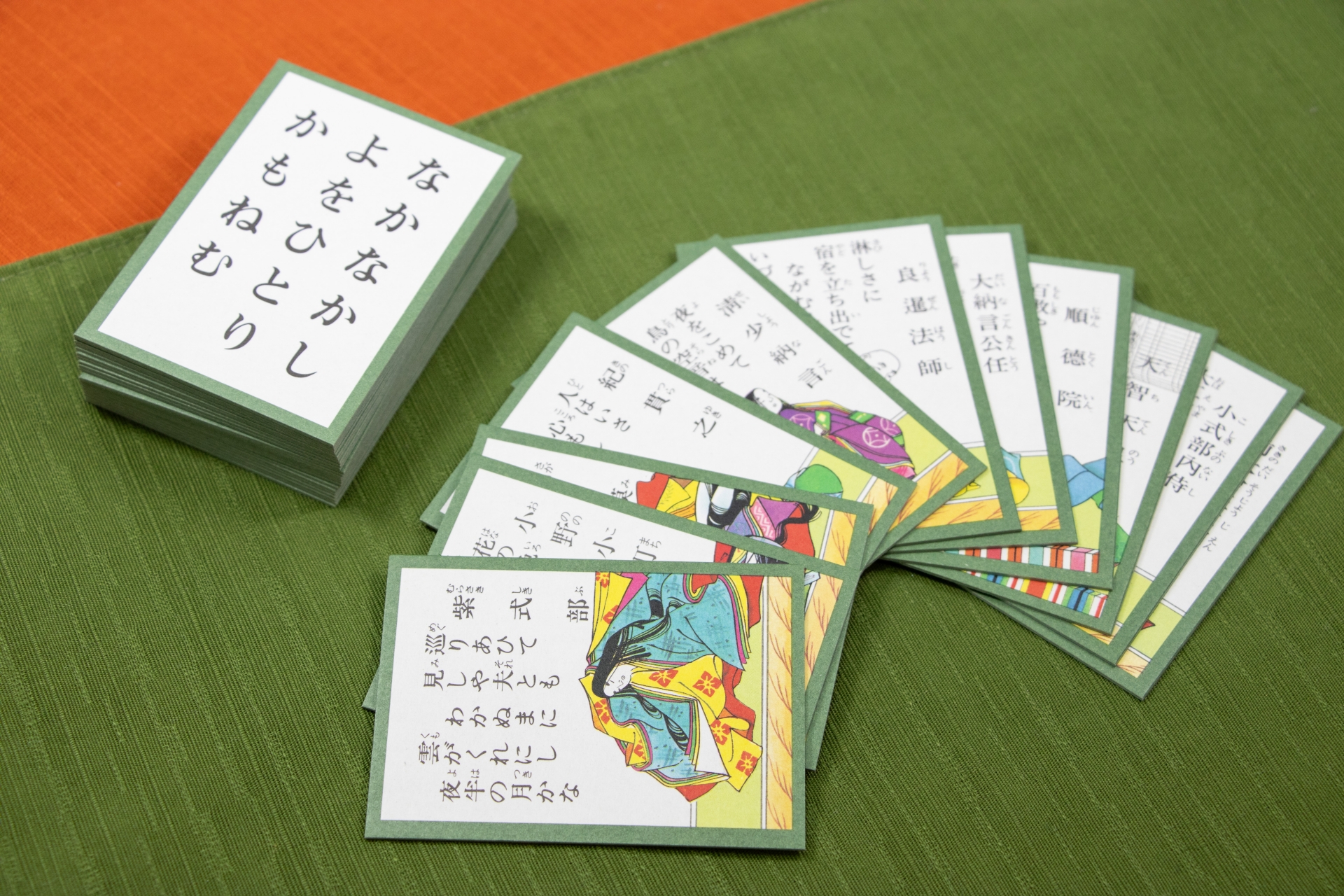

Karuta is a poetic card game consisting of two card sets:

- Yomifuda (reading cards): Each contains a complete classical poem.

- Torifuda (grabbing cards): These show only the second halves of the poems.

A reader recites the poems aloud, and players compete to swipe the correct torifuda. The game demands sharp memory, quick reflexes, and familiarity with waka poetry.

Why it’s a New Year tradition

Hyakunin-Isshu karuta has long been a staple of New Year gatherings because the themes of the poems—nature, seasons, and emotion—resonate with reflection and renewal.

Historical roots

Its structure of matching corresponding pieces traces cultural lineage back to Heian-era kai-awase, where noblewomen matched pairs of elegant clam shells—the earliest form of poetic or pictorial matching games.

Modern practice

Casual family sets are beginner-friendly, while competitive karuta—popularized worldwide by the anime Chihayafuru—is a highly athletic sport with major tournaments held every January.

Hanetsuki (羽根つき)

Hanetsuki resembles badminton without a net. Players use a decorated wooden paddle (hagoita) to hit a feathered shuttlecock (hane). It may be played solo or as a rally between two people.

Symbolic meaning: Protection from evil

Traditionally, hanetsuki was believed to ward off evil spirits and protect children from illness.

The shuttlecock—often made from the seed of the mukuji tree, which itself carried protective symbolism—represented driving away misfortune, especially insects and disease. A child who kept the shuttle bouncing without dropping it was said to enjoy a “healthy year ahead.”

Modern decline and decorative use

With limited open spaces, children play hanetsuki far less today. However, elaborately designed hagoita featuring kabuki actors, beautiful women, or modern characters remain a beloved New Year ornament. Tokyo’s famous Hagoita Fair in Asakusa draws visitors every December.

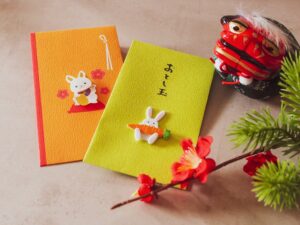

Fukuwarai (福笑い)

Meaning “lucky laughter,” fukuwarai is a blindfolded face-building game dating back to the late Edo period. Players place separate cutouts of facial features—eyes, eyebrows, nose, mouth—onto a blank face while blindfolded, resulting in humorous combinations.

Symbolism and appeal

The laughter created by the game symbolizes welcoming happiness and good fortune into the household. The simplicity of the rules makes it accessible for families, schools, cultural events, and international classrooms.

DIY ideas

Print a blank face on paper, cut out facial parts, and reuse them with magnets or lamination for classrooms or group activities.

Takoage (凧揚げ / Kite Flying)

Kite flying is one of the oldest New Year customs in Japan. Children send their wishes into the sky by flying tako in open fields or beaches.

Historical significance

In the Edo period, kite designs became increasingly elaborate, featuring folklore figures, heroes, and auspicious patterns. Some regions developed giant kites as symbols of strength and prosperity.

Modern situation

Due to safety rules and reduced open spaces, kite flying has declined in cities, but traditional festivals continue in places like Hamamatsu. Small kites are still sold at New Year fairs.

Global parallels

Like Chinese New Year kite traditions or Western springtime kites, Japanese kite flying symbolizes the elevation of aspirations and spiritual renewal.

Sugoroku (すごろく / Japanese Board Game)

Sugoroku is a simple roll-and-move board game, somewhat similar to Snakes & Ladders. Players advance by dice rolls and encounter luck-based bonuses or penalties.

Why it became a New Year classic

In the early 20th century, printed sugoroku sheets were included as holiday bonuses in magazines and newspapers. Families would gather around the table to play after shrine visits or New Year meals.

Variations

Themes include folk tales, geography, historical heroes, or modern characters. Its simplicity makes it ideal for mixed groups and parties.

Koma (独楽 / Spinning Tops)

Koma are traditional wooden spinning tops found throughout Japan. Children compete in techniques or in how long they can keep a top spinning.

Symbolic meaning

Spinning tops are associated with setting the year into smooth motion—a metaphor for stability and good fortune in the coming year.

Traditional vs. Modern Tops

| Feature | Traditional Koma | Modern Tops (e.g., Beyblade) |

| Material | Wood | Plastic/Metal |

| Technique | Hand-twisted string or direct spin | Launcher-based spin |

| Purpose | Skill, symbolism | Battles, collection |

| Cultural Meaning | New Year charm | Pop-culture entertainment |

Traditional koma remain popular at children’s museums, temple fairs, and seasonal market stalls.

The Meaning Behind the Games: Luck, Renewal, and Tradition

Traditional New Year games carry deeper cultural symbolism:

- Hanetsuki protects children from evil spirits and illness.

- Kite flying sends wishes upward for the year ahead.

- Fukuwarai invites good fortune through shared laughter.

- Karuta nurtures appreciation of classical poetry and heritage.

Across all games, common themes include:

- Welcoming good luck

- Celebrating renewal

- Strengthening family unity

- Passing down tradition

These games highlight that joy, humor, and community are as essential as prayer and ritual in welcoming a prosperous New Year.

How to Experience Japanese New Year Games Today (For Locals and Visitors)

Even if you’re visiting Japan or living abroad, there are many ways to enjoy these traditions.

Where to buy traditional games

- In Japan: Don Quijote, Tokyu Hands, 100-yen shops, department-store New Year sections

- Online: Rakuten, Amazon Japan, cultural specialty stores

- Seasonal fairs: Asakusa Hagoita Market, local temple fairs

Festivals and workshops

During the first week of January, many cities host events featuring:

- Karuta demonstrations

- Kite-making and kite-flying

- Fukuwarai corners for kids

- Koma spinning workshops

At home or abroad

- Printable fukuwarai sets

- English-friendly karuta decks

- Portable sugoroku boards

- Japanese New Year–themed game nights for classes or cultural groups

Modern limitations and alternatives

If kite flying or hanetsuki isn’t feasible:

- Try indoor koma or sugoroku

- Use desk-friendly mini kites

- Display hagoita as seasonal decorations

Conclusion: Why These Games Still Matter Today

Traditional Japanese New Year games remain beloved not out of obligation, but because they bring joy, connection, and cultural meaning. In an increasingly digital world, these analog activities offer refreshing opportunities for families to bond, appreciate tradition, and greet the New Year with optimism.

Whether you’re traveling to Japan, teaching culture, or celebrating at home, trying even one of these games—karuta, fukuwarai, or koma—can create lasting memories and deepen your appreciation of Japanese heritage.

Why not make one of them part of your next New Year celebration?