In the early Edo period, Japan witnessed an extraordinary political innovation: Sankin Kōtai (参勤交代), or the “Alternate Attendance System.” Instituted formally in 1635 under Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, it required each daimyō (feudal lord) to alternate residence between his home domain and Edo—the shogun’s capital, now Tokyo.

Far from being a mere bureaucratic routine, Sankin Kōtai was a sophisticated political mechanism designed to bind the entire country together after centuries of civil war. By compelling daimyō to travel vast distances with large entourages and maintain costly residences in both Edo and their home domains, the Tokugawa regime achieved unparalleled political control, economic stimulation, and social cohesion.

This article explores how Sankin Kōtai developed from medieval precedents, how it functioned in practice, and how its legacies still shape Japan today—from the roads that knit the country together to the rise of Edo as the world’s largest premodern metropolis.

Origins and Purpose of Sankin Kōtai

Historical Background

The idea behind Sankin Kōtai did not emerge suddenly in the Edo period. Its roots extend deep into Japan’s medieval past.

During the Kamakura shogunate (1185–1333), samurai vassals were required to perform banyaku—a duty rotation system that obligated them to serve in Kamakura for specific periods. This practice ensured loyalty and allowed the shogunate to monitor its retainers directly.

Under the Muromachi shogunate (1336–1573), a similar practice continued. Regional governors, or shugo daimyō, were expected to alternate their residence between their provincial territories and Kyoto, a system often referred to as zaikyō kōtai (“alternate presence in the capital”).

The Tokugawa shogunate later refined and institutionalized these earlier customs into a nationwide policy. In 1635, Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu issued an edict that formally required every daimyō to alternate residence between Edo and his domain on a regular basis.

This marked the beginning of Sankin Kōtai as one of the Edo period’s most significant tools for maintaining centralized peace after centuries of civil conflict.

The Four Main Purposes

Political Control:

The system was primarily designed to prevent rebellion. By forcing lords to spend much of their time in Edo, the shogunate curtailed their ability to organize uprisings or consolidate military power at home.

Economic Drain:

Maintaining two residences and organizing grand processions imposed enormous financial strain on the daimyō, deliberately reducing their wealth and independence.

Centralization:

The policy drew population, commerce, and culture toward Edo, reinforcing its position as Japan’s political and economic heart.

Surveillance and Hostage Policy:

The rule that required a daimyō’s wife and heir to live permanently in Edo effectively turned them into hostages, ensuring the lord’s loyalty through family leverage.

Who Carried Out Sankin Kōtai

The Sankin Kōtai system primarily applied to daimyō who ruled domains producing at least 10,000 koku of rice (about 5 million liters). Yet the scale of these journeys far exceeded a lord’s personal entourage—each procession resembled a moving court.

A single Sankin Kōtai journey often included:

- Samurai retainers and attendants

- Servants, laborers, and porters

- Horses, palanquins, and supply wagons

- Craftsmen and merchants who provided food, clothing, and lodging

The Maeda clan of the Kaga Domain was famous for its magnificent processions, sometimes involving over 3,000 retainers. Similarly, the Satsuma and Sendai domains maintained massive, disciplined entourages that projected their power and loyalty while stimulating local economies along the routes.

Mechanisms: How the System Worked

Under Sankin Kōtai, every daimyō alternated annually between his domain and Edo. During his Edo year, he performed duties to the shogunate, attended ceremonies, and maintained his residence in the capital. The following domain year was spent administering his local territory.

Cycle Example:

| Year | Location | Purpose |

| 1 | Domain | Local governance |

| 2 | Edo | Shogunal service |

| 3 | Domain | Administration |

| 4 | Edo | Ceremony and attendance |

The daimyō’s family—especially his wife and heir—remained in Edo permanently, serving as de facto hostages.

Travel between Edo and the provinces often took weeks or even months, depending on distance. The processions followed the Gokaidō (Five Highways), the most famous being the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō routes. Along these roads, official post stations (shukuba), checkpoints, and relay systems thrived to accommodate the steady flow of travelers.

The Cost of Sankin Kōtai

The economic burden placed on daimyō was immense. Each procession required meticulous organization, elaborate attire, lavish gifts, and months of travel-related expenses.

| Domain | Distance to Edo | Cost per Trip (Ryō) | Modern Equivalent (¥) | Approx. USD |

| Kaga (Maeda) | 450 km | 5,500 | ¥550,000,000 | $3.7M |

| Sendai (Date) | 350 km | 3,800 | ¥380,000,000 | $2.5M |

| Small Domain | 200 km | 1,200 | ¥120,000,000 | $0.8M |

Such expenses were intentional. By exhausting daimyō treasuries, the shogunate curtailed any potential for military buildup or rebellion.

At the same time, these journeys stimulated the national economy. Inns, tailors, craftsmen, and merchants along the highways prospered thanks to the constant demand created by the processions. Edo’s service industries also flourished, feeding and housing thousands of retainers each year.

Economic and Social Effects

Beyond its political purpose, Sankin Kōtai transformed the economy and society of Edo-period Japan. The regular movement of people, money, and goods created interregional networks and standardized trade practices across the country.

Key Impacts:

Economic Ripple Effect:

Constant travel encouraged road construction, bridge maintenance, and a thriving service industry along the highways.

Urban Expansion:

Edo’s population surpassed one million by the 18th century, making it one of the world’s largest cities.

Cultural Exchange:

As daimyō, samurai, artisans, and merchants traveled between regions, they spread regional cultures, crafts, cuisines, and dialects throughout Japan.

The system thus served as both an engine of control and a vehicle of connectivity, fostering what historians often call Japan’s “proto-modern economy.”

Cultural and Infrastructural Legacy

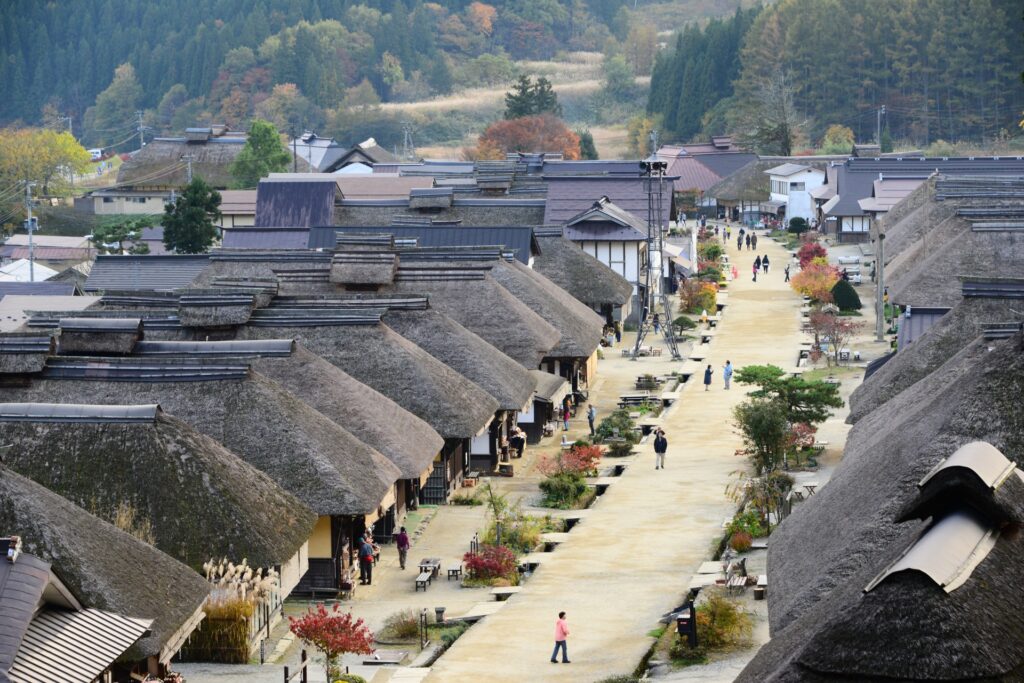

The highways, inns, and post towns established under Sankin Kōtai remain integral to Japan’s cultural geography. Major routes like the Tōkaidō and Nakasendō became the nation’s arteries of commerce and communication.

Historic post towns such as Hakone, Narai-juku, and Tsumago still preserve Edo-period charm. Modern reenactments of daimyō processions attract tourists and celebrate the pageantry of the era.

The system also left intangible legacies—blended dialects, cross-regional artistic styles, and shared culinary influences—that helped forge a unified Japanese identity.

Decline and End of the System

By the mid-19th century, Japan faced growing external pressures from Western powers and deepening financial distress at home. Maintaining Sankin Kōtai became increasingly impractical.

In 1862, the Tokugawa government issued a relaxation decree, allowing daimyō to visit Edo less frequently. With the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the abolition of the feudal domain system (han), Sankin Kōtai came to an official end—closing a chapter that had lasted for more than two centuries.

Why Sankin Kōtai Still Matters Today

The legacy of Sankin Kōtai extends far beyond the Edo period. The infrastructure and logistics systems it established laid the foundation for Japan’s modernization in the Meiji era.

Tokyo’s enduring dominance as Japan’s political and economic center is a direct continuation of the centralization initiated by the Tokugawa shogunate.

Culturally, Sankin Kōtai survives in festivals, museums, and reconstructed daimyō processions. Modern travelers can walk along Edo-period highways, stay in preserved inns, and relive the journeys of samurai through Japan’s scenic heartlands.

Conclusion: Legacy of Control and Connection

The Sankin Kōtai system was both a masterful instrument of political control and a catalyst for Japan’s unification and modernization. Its fourfold aims—control, economic drain, centralization, and surveillance—reshaped Japan’s geography, economy, and cultural fabric.

Even today, its traces endure: in Tokyo’s primacy, in the transportation routes that still outline Japan’s map, and in the cultural memory of an era when loyalty, spectacle, and logistics defined the state.

From control to connection, the legacy of Sankin Kōtai shows how governance can shape a nation far beyond its rulers.