Visiting a Japanese shrine or temple, you’ll likely see people shaking wooden boxes, unfolding small slips of paper, or hanging colorful wooden plaques covered in handwritten wishes. These are omikuji (fortune slips) and ema (wooden wish boards)—two beloved traditions that connect people with Japan’s spiritual culture.

Both offer a glimpse into the country’s deep sense of fate, gratitude, and hope. Whether you’re exploring Tokyo’s Meiji Jingū or a quiet countryside shrine, this guide will help you understand what these customs mean, how to take part respectfully, and how to make your experience memorable.

What Are Omikuji and Ema?

At their core, omikuji and ema are tools for communication—one with fate, the other with the gods. Both are found in Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples across Japan, reflecting centuries of belief that divine guidance can be sought through tangible acts of faith.

Omikuji are randomly drawn paper fortunes, while ema are wooden plaques on which visitors write their wishes or expressions of thanks. Each practice carries its own meaning and ritual, yet they complement one another beautifully: the omikuji reveals what destiny holds, and the ema allows you to shape your hopes for the future.

Their origins trace back to Japan’s ancient spiritual practices. Omikuji began as a form of divination used by monks and priests to interpret divine will, while ema evolved from the offering of real horses—once considered messengers of the gods—to symbolic wooden “horse tablets” (the word ema literally means “picture horse”).

Below is a quick traveler-friendly comparison of the two traditions:

| Item | Definition | Purpose | Typical Cost | Common Ritual | What to Do After |

| Omikuji | Paper fortune slip drawn at shrine or temple | To learn one’s luck or divine guidance | ¥100–¥200 | Shake canister, draw numbered stick, match to fortune paper | Keep if good luck; tie to rack/tree if bad luck |

| Ema | Wooden plaque for writing wishes | To express hopes or gratitude to the gods | ¥300–¥800 | Write wish, hang on shrine rack | Leave at shrine for gods to receive |

Together, these customs form an accessible and heartfelt way for visitors to engage with Japan’s living traditions—no prior religious knowledge required.

Omikuji: The Fortune Slip

Omikuji (おみくじ) literally means “sacred lot.” They are small strips of paper that reveal a person’s fortune, traditionally drawn at temples or shrines. To draw one, you usually shake a wooden or metal cylinder until a numbered stick slides out. The number corresponds to a drawer or envelope containing your fortune.

In recent years, you might also find vending machines or digital omikuji, especially at large urban shrines. Regardless of the method, the excitement is the same—the mystery of what the gods might reveal.

Typical omikuji fortunes include ranks such as:

- Daikichi (大吉) — Great Blessing / Excellent Luck

- Kichi (吉) — Good Luck

- Chūkichi (中吉) — Middle Luck

- Shōkichi (小吉) — Small Luck

- Suekichi (末吉) — Future Luck / Luck to Come

- Kyō (凶) — Bad Luck

Your omikuji may include predictions about health, love, travel, business, studies, and more.

If your fortune is good, you can take it home as a charm for continued luck. If it’s bad, it’s customary to fold and tie it to a designated rack or tree within the shrine grounds—symbolically “leaving bad luck behind.”

Typical cost: around ¥100–¥200 (≈$1–$2)

How to draw omikuji (step-by-step):

- Approach the omikuji stand and place a small coin in the donation box.

- Shake the cylinder until a numbered stick comes out.

- Match the number to the corresponding drawer or paper slip.

- Read your fortune (some shrines offer English translations).

- Keep or tie your omikuji depending on the result.

- Bow lightly to show respect before leaving.

It’s a simple yet deeply enjoyable ritual—one that makes every visit unique.

Ema: The Wooden Wish Tablet

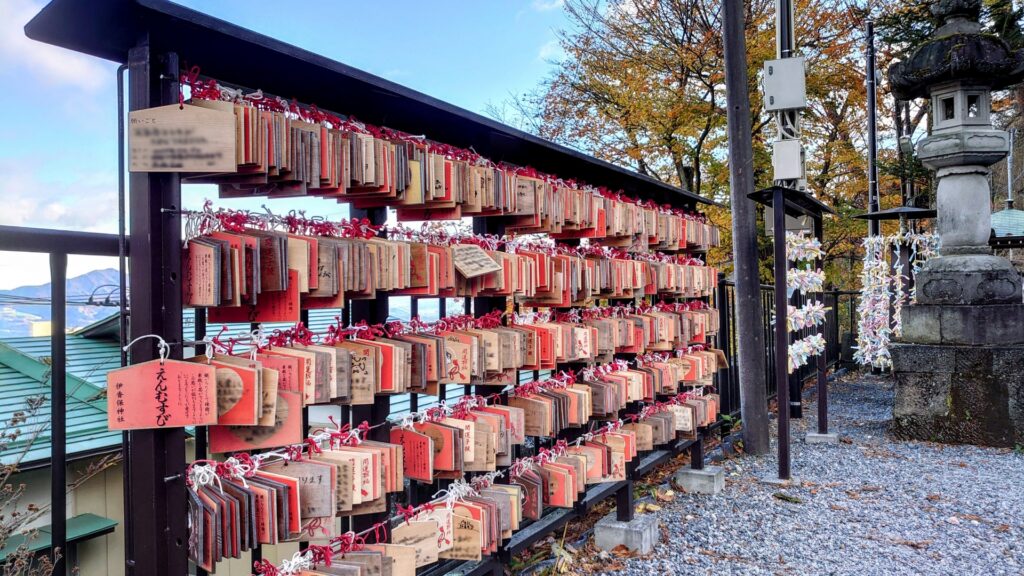

Ema (絵馬) are small wooden plaques where worshippers write their wishes, prayers, or words of gratitude. After writing, they’re hung on special racks at the shrine, allowing the gods (kami) to “receive” the messages.

The practice dates back over a thousand years. In ancient times, people would donate live horses to shrines as offerings, since horses were thought to carry messages to the gods. Over time, this evolved into wooden tablets painted with horses, then into today’s beautifully designed ema that feature seasonal or local imagery.

You can find ema in countless variations:

- Zodiac animals representing the current year

- Local motifs like Mount Fuji, cherry blossoms, or famous deities

- Anime collaborations, where characters appear on the plaques (ita-ema, or “painfully cute ema,” are popular among fans)

- Custom shapes—heart-shaped for love, owl-shaped for wisdom, etc.

How to use an ema:

- Purchase one from the shrine’s offering counter (¥300–¥800).

- Write your wish neatly on the blank side. Many shrines provide pens or markers.

- Include your name or initials if you like.

- Hang it on the designated rack, facing outward.

You can write about anything—success in studies, good health, love, safe travels, or gratitude for blessings received. The key is sincerity.

Unlike omikuji, ema are left at the shrine, where priests later ritually burn them as an offering, releasing your wish to the divine.

How to Experience Omikuji and Ema on Your Visit

To make the most of your shrine visit, it helps to follow the traditional order of etiquette. Here’s a simple flow to ensure your experience is both enjoyable and respectful:

- Approach the torii gate (the red shrine gate) and bow lightly before entering—it marks the boundary between the sacred and the secular.

- Purify your hands and mouth at the temizuya (water basin): rinse your left hand, then right, then take a sip from your left hand and rinse lightly.

- Offer a small coin (usually 5 yen, considered lucky) at the main hall.

- Ring the bell, bow twice, clap twice, make your silent prayer, and bow once more.

- Draw your omikuji if available, and read your fortune.

- Write your ema with your wish or message.

- Enjoy the atmosphere—take photos respectfully, thank the staff, and leave quietly.

Traveler checklist:

- Coins (¥100 and ¥5 are ideal for offerings)

- A pen (some shrines provide, but not all)

- Translation app (if English versions aren’t available)

- Awareness of others—avoid blocking worshippers or taking loud photos

This small ritual can transform your visit from a quick photo stop into a truly meaningful cultural exchange.

Where to Find English-Friendly Shrines and Unique Variations

Many major shrines in Japan now welcome international visitors with English explanations and multilingual omikuji.

Recommended spots:

- Meiji Jingū (Tokyo) — Offers English omikuji focusing on spiritual messages rather than luck rankings.

- Senso-ji (Asakusa, Tokyo) — Features traditional numbered drawers and affordable omikuji (¥100).

- Fushimi Inari Taisha (Kyoto) — Fox-themed ema and red torii motifs; omikuji available in English.

- Kasuga Taisha (Nara) — Famous for its deer-shaped omikuji, reflecting the sacred deer that roam freely in its grounds.

- Kinkakuji (Kyoto) — Beautiful ema featuring the Golden Pavilion.

You may also find creative variations:

- “Robot omikuji” machines that dispense fortunes in multiple languages.

- Cute character omikuji shaped like cats, owls, or Daruma dolls.

- Ema walls covered in anime art—especially near Akihabara or otaku pilgrimage sites.

Don’t hesitate to ask shrine staff for assistance; they are usually kind and used to helping international visitors.

Etiquette, Manners & What to Avoid

Japanese shrines are sacred spaces, and simple mindfulness goes a long way. Here are key points of etiquette to remember when enjoying omikuji and ema:

Do’s:

- Speak quietly and move calmly.

- Use both hands when offering coins or taking items.

- Take photos respectfully (avoid capturing people praying).

- Write thoughtful, appropriate wishes—avoid jokes or offensive language.

- Tie your bad-luck omikuji at the designated place only.

Don’ts:

- Don’t place coins directly on altars or statues.

- Don’t take ema home—leave them for the gods.

- Don’t crumple or throw away omikuji, even bad ones.

- Don’t eat, drink, or smoke within shrine grounds.

- Don’t write others’ names without consent.

If you draw a bad fortune (kyō), tying it to the provided rack helps “leave” the bad energy behind. But if you get a good fortune, feel free to keep it as a lucky charm.

By following these small gestures, you’ll show deep respect for Japan’s culture—and earn warm smiles from the locals.

Beyond the Basics: Deeper Insights & Trends

Both omikuji and ema have evolved with the times, blending ancient belief with modern creativity.

Historically, omikuji were drawn only by monks using sacred lots for major decisions, like imperial matters or shrine rituals. Over the centuries, the practice became more public, turning into a popular form of personal fortune-telling.

Ema, meanwhile, grew from religious offerings into community art—each shrine developing its own distinctive designs. Today, visitors enjoy collecting ema as cultural souvenirs, even photographing walls filled with hundreds of wishes from around the world.

Modern trends include:

- Anime and pop-culture ema (ita-ema): fans draw or print their favorite characters alongside their prayers.

- Seasonal omikuji: New Year’s hatsumōde season sees massive crowds drawing fortunes for the year ahead.

- Regional specialties: Some shrines sell heart-shaped ema for love, fish-shaped omikuji for prosperity, or even “fortune chocolates.”

- Digital omikuji: Smartphone-based or vending machine-style omikuji offer instant translations and convenient access.

Despite modernization, the purpose remains the same—seeking connection, reflection, and gratitude. These evolving forms show how tradition continues to live and breathe in modern Japan.

Conclusion

Omikuji and ema are far more than tourist novelties—they are living symbols of Japan’s spirituality, community, and hope. By taking a moment to draw a fortune or write a wish, you’re joining millions of others who, across generations, have turned to the gods for guidance and peace of mind.

As a traveler, participating respectfully in these rituals offers a rare chance to experience authentic Japan beyond the surface. It’s not about whether your fortune says “great luck” or “small luck,” but about pausing, reflecting, and connecting—to the place, the people, and the unseen forces that make Japan’s culture so deeply moving.

So next time you step beneath a red torii gate, take a coin, draw your omikuji, and hang your ema. Your journey may just bring more fortune—and meaning—than you expected.