Define what “ukiyo-e” means in clear English, unpack the double meaning of ukiyo, then ground readers with quick examples (Hokusai, Hiroshige) and how the term is used today. Promise a pronunciation guide, a mini-glossary, and simple visuals explaining production and subjects.

What does “ukiyo-e” literally mean?

At its simplest, ukiyo-e breaks down into three parts: ukiyo (浮世) and e (絵). The compound ukiyo consists of uki (浮, floating/transient) + yo (世, world/era/society). Add e (絵, picture/painting), and the phrase renders cleanly in English as “picture(s) of the floating world.” But the seeming simplicity hides a cultural pivot: in medieval and early early-modern Japanese Buddhism, ukiyo could signify the sorrowful, impermanent world; by the Edo period (1603–1868), the same sounds tilted toward an urban ethos of fleeting pleasures in the licensed quarters and theater districts. Ukiyo-e, then, are images that both acknowledge life’s transience and revel in the stylish moment—ephemeral yet dazzling.

Quotable takeaway: Ukiyo-e literally means “pictures of the floating world.” The phrase captures a double valence: Buddhist impermanence and Edo-period pleasure culture.

The Buddhist roots vs. Edo-period shift

Originally, ukiyo in Buddhist-inflected Japanese writing pointed to a “gloomy/afflicted world” characterized by impermanence and suffering—an outlook that counseled detachment. In the early modern metropolis of Edo, however, merchants and townspeople refashioned the word into an aspirational lifestyle: savor what floats by—music, fashion, kabuki, witty conversation—because it will soon vanish. This semantic flip mirrors the city’s growth, the rise of a moneyed chōnin class, and the emergence of licensed pleasure quarters such as Yoshiwara. Artists, publishers, and writers capitalized on the new sensibility, creating images that transformed everyday entertainments into icons.

Sidebar — Same sounds, different worlds

| Aspect | Buddhist ukiyo (憂き世) | Edo pleasure-world ukiyo (浮世) |

| Core sense | Sorrowful, impermanent world; reason for detachment | Floating, fashionable world; savor the fleeting |

| Tone | Moral-philosophical, cautionary | Urban, witty, hedonistic |

| Typical spaces | Temples, didactic texts | Yoshiwara, kabuki theaters, teahouses |

| Approx. period | Medieval to early Edo usage | Mid–late Edo popular culture |

Quick pronunciation guide (with IPA)

Break it into four beats: u-ki-yo-e. In careful English approximation, you’ll often see /ˌuːkiːˈjoʊ.eɪ/ (OO-kee-YOH-eh). In Japanese phonetics, it’s closer to [ɯ.kʲi.jo.e]—no stress accent, each vowel sounded clearly, and the final -e is not silent. Common mistakes include saying “yukio,” dropping the final -e, or stressing the first syllable like “OO-kee-yo.” A reliable memory hook: “oo-KEY-yo-eh—four clean vowels in a row.” If you can say karaoke or edamame with the last vowel, you can say ukiyo-e.

Is ukiyo-e a technique or a genre?

Ukiyo-e is best understood as a genre (or style) of images—prints and paintings—that flourished mainly in the Edo period. While most people encounter ukiyo-e as woodblock prints, the term does not equal “woodblock” alone. There are hand-painted works (called nikuhitsu-ga) within the ukiyo-e sphere, but the medium’s spectacular reach came from collaborative woodblock printmaking published and distributed at scale. Key to this ecosystem was the publisher, who commissioned designers (artists), hired carvers and printers, managed censorship, and brought images to market. So: woodblock printing is the principal vehicle, but ukiyo-e names the imagery and cultural focus—beauties, actors, landscapes, and the floating world’s fashions—rather than a single technique.

How woodblock printing made ukiyo-e go viral in Edo

Multi-color woodblock printing—especially nishiki-e (brocade prints) introduced in the mid-18th century—allowed publishers to release vibrant, affordable images in the thousands. Because each color required its own carved block, publishers coordinated teams to keep registration precise and effects consistent. This industrialized artistry made stars of actors and courtesans, spread fashion trends across neighborhoods, and turned travel series into armchair tourism. The result was a proto-pop culture: collectible, topical, and shareable, long before social media.

Production flow (compact):

Publisher → Designer (eshi) → Key block (horishi) → Color blocks → Printer (surishi) → Quality checks & seals → Shops & stalls

Production steps at a glance: how ukiyo-e were made (clear list)

Note: Ukiyo-e includes both hand-painted works (nikuhitsu-ga) and woodblock prints. The latter drove mass popularity.

- Publisher (hanmoto): selects themes, finances projects, secures paper and pigments, plans the edition, schedules releases, and navigates censorship where applicable.

- Designer (eshi): creates the master drawing (hanshita-e), often on thin paper; this sheet guides carving and is typically sacrificed during block preparation.

- Block carver (horishi): pastes the drawing face-down on a cherrywood plank and carves the key block (outlines) plus a suite of color blocks; precision and line sensitivity are critical.

- Printer (surishi): inks each block and prints in sequence on washi using a hand tool (baren); maintains kento registration, controls moisture, and executes effects like bokashi (graded wash), embossing, or mica.

- Seals & distribution: applies censor/publisher/date seals (in relevant periods), inspects quality, then ships to bookstores, stalls, and itinerant sellers.

- Hand-painted ukiyo-e (nikuhitsu-ga): pigments and ink applied directly to paper or silk; mounted as hanging scrolls or albums; unique rather than editioned.

What did ukiyo-e depict? Core subjects and themes

From the start, ukiyo-e pictured the people and pleasures of the city: beauties (bijin-ga) advertising fashions and the allure of famous houses; kabuki actors (yakusha-e) immortalizing star turns and signature poses; and parades, festivals, and seasonal outings that mapped urban life. Over time the repertoire widened to include landscapes, travel routes, famous places (meisho-e), flora and fauna (kachō-e), warriors (musha-e), and erotica (shunga) sold discreetly to adult audiences. A few thumbnail anchors help: Katsushika Hokusai for inventive composition and nature studies; Utagawa Hiroshige for lyrical travel views; Kitagawa Utamaro for intimate portraits of beauties; and Tōshūsai Sharaku for psychologically sharp actor prints. Across subjects, the constant is the celebration of moments that float—fashions change, actors age, seasons turn—and prints preserve the shimmer.

The late rise of landscapes and global fame

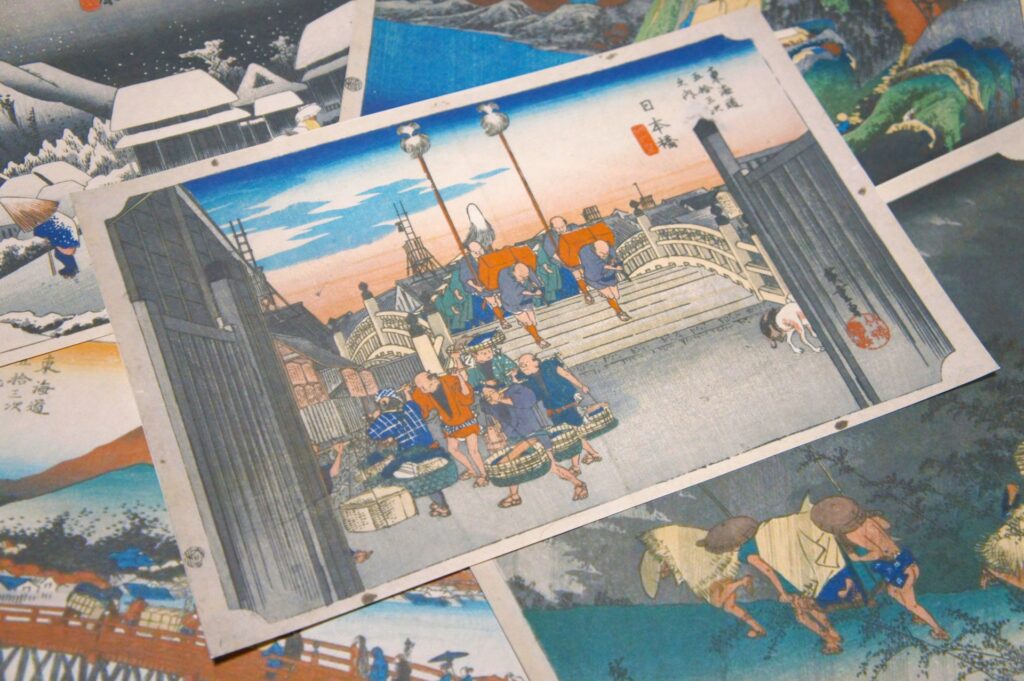

Landscapes were not the initial focus of ukiyo-e; they bloomed spectacularly in the 19th century, especially with Hokusai’s series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” and Hiroshige’s travel sets like “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō.” Hokusai’s Great Wave—a towering crest framing a distant Fuji—became an international emblem of Japanese art, shaping Western artists’ sense of composition, cropping, and pattern. This cross-cultural spark fed Japonisme in Europe, influencing Impressionists and Post-Impressionists who admired the prints’ flat color planes, daring viewpoints, and everyday subjects. In short, late Edo landscape ukiyo-e didn’t just document travel; it rewired how the world pictured modern life.

Genres within ukiyo-e: a quick list (what artists depicted)

- Bijin-ga (beauties): Courtesans, geisha, and stylish townspeople; fashion plates that also advertise famous quarters. Rep. artist: Kitagawa Utamaro.

- Yakusha-e (actor prints): Kabuki stars in role; dynamic mie poses and close-ups; fan culture before photography. Rep. artist: Tōshūsai Sharaku.

- Fūkei-ga / Meisho-e (landscapes / famous places): Travel routes, seasons, celebrated vistas, often serialized. Rep. artists: Hokusai, Utagawa Hiroshige.

- Musha-e (warriors): Epic battles, samurai heroes, and folklore champions; moral drama and bravura line.

- Sumō-e (sumo): Wrestlers, bout scenes, rankings; sports celebrity culture in print.

- Kachō-e (flowers & birds): Nature studies and poetic vignettes; elegant gifts and décor.

- Shunga (erotica): Explicit adult imagery sold privately; educational/art-historical context required for display.

- Yōkai & literature scenes: Monsters, ghosts, and classics from Genji to Kabuki tales; visual storytelling.

- Uchiwa-e and surimono: Fan prints and deluxe small-format gifts, often with poems or special printing effects.

Mini-glossary: terms readers see with “ukiyo-e”

- nishiki-e (錦絵): “Brocade prints.” Multi-color woodblock prints using separate blocks for each hue; mainstream by the mid-18th century.

- benizuri-e (紅摺絵): Early two- or three-color prints highlighted with pinkish beni; transitional step before full polychrome.

- aizuri-e (藍摺絵): Prints dominated by blue pigments (notably Prussian blue), popular in the 1820s–30s.

- bokashi (ぼかし): Hand-applied gradient effect on the block or paper, creating soft fades (e.g., dawn skies, mist).

- hanshita-e (版下絵): The artist’s master drawing pasted onto the woodblock to guide carving; typically destroyed in the process.

- tate-e / yoko-e (縦絵/横絵): Vertical vs. horizontal print orientations; often associated with specific series or subjects.

- censor/publisher/date seals: Marks that indicate approval, publisher identity, and approximate date; useful for dating and authentication.

Timeline: from rise to decline

- Early 17th century: Proto-ukiyo-e paintings and single-color prints emerge in Edo, tied to the pleasure quarters and theater.

- Mid–late 17th century: Expansion of subjects; improvements in carving and paper support wider distribution.

- Mid-18th century: Breakthrough of nishiki-e (polychrome) standardizes rich color printing; celebrity culture accelerates.

- Early–mid 19th century: Peaks in landscape and travel series (Hokusai, Hiroshige); technical refinements (Prussian blue, sophisticated bokashi).

- Late 19th century (Meiji): Modernization, new media (photography/lithography), and shifting tastes contribute to decline in traditional ukiyo-e production.

- Late 19th–early 20th centuries: Powerful Western reception (Japonisme), influencing composition and color in Impressionism and beyond.

- 20th century onward: Revival movements (shin-hanga, sōsaku-hanga) reinterpret the woodblock medium under modern conditions.

Using the term correctly today

Do’s & Don’ts

- Use “ukiyo-e” for Edo-to-Meiji images tied to the floating-world sensibility, whether printed or hand-painted; specify woodblock print vs. painting when you can.

- Don’t call every Japanese print “ukiyo-e.” Later movements (shin-hanga, sōsaku-hanga) and devotional or academic prints may belong to different categories.

- Do distinguish original impressions from later reprints or recut editions; look for paper quality, pigment character, and period seals.

- Don’t mix up “ukiyo” (the idea of the floating world) with “ukiyo-e” (images of it). One is a worldview; the other is a body of artworks.

Museum/teacher checklist

- Can you state the literal meaning (pictures of the floating world) and explain the Buddhist vs. Edo double sense?

- Can you identify whether an example is a print or a hand-painted work?

- Can you outline the division of labor (publisher–designer–carver–printer)?

- Can you place a work into a genre (beauty, actor, landscape, warrior, nature, etc.)?

- Can you read seals to estimate date/publisher when relevant, and note if a work is a later reprint?

Conclusion

Ukiyo-e literally means “pictures of the floating world,” a phrase that simultaneously carries the Buddhist sense of impermanence and the Edo-period turn toward urban pleasure and style. The category embraces both hand-painted works and woodblock prints, though its mass appeal was propelled by publisher-led, collaborative printmaking in which designers, block carvers, and printers coordinated precise registration and special effects. Its subjects range widely—from beauties and actors to landscapes, warriors, sumo, nature studies, erotica, and folklore—with landmark series and signature artists anchoring each thread. Used today, the term deserves precision: distinguish ukiyo (the worldview) from ukiyo-e (the images), and be alert to differences between original impressions and later reprints or recut editions. With these distinctions in mind—the double meaning, the production pipeline, the genre map, and careful terminology—readers, museum-goers, students, and teachers can navigate exhibitions and scholarship with clarity and confidence.