Chikamatsu Monzaemon is one of Japan’s most celebrated playwrights, whose works laid the foundation for modern Japanese theater. Often referred to as the “Shakespeare of Japan,” his emotionally charged jōruri (puppet theater) and kabuki dramas captured the complexities of love, honor, and human suffering. This article explores his life, his most important works, his impact on Edo-period theater, and his relevance in the contemporary world.

Who Was Chikamatsu Monzaemon?

Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) was one of Japan’s most influential dramatists, celebrated for his profound contributions to both Bunraku (puppet theater) and Kabuki. Born Sugimori Nobumori in Echizen Province (modern-day Fukui Prefecture), he was the son of a low-ranking samurai who later became a ronin. His early years were spent in Kyoto, where he was exposed to court life and literary arts through his association with aristocratic circles. This exposure provided Chikamatsu with a unique blend of classical education and real-world insight into human behavior and emotion.

Chikamatsu began his career writing scripts for Kabuki around 1683, but he eventually found his creative home in Bunraku. By the early 1700s, he was collaborating with the famed Bunraku chanter Takemoto Gidayū in Osaka, producing some of the most iconic works in Japanese theatrical history. His deep understanding of human psychology and his mastery of narrative structure made him a towering figure in the world of Edo-period drama. His career represents a bridge between the elite cultural world of the court and the popular entertainment of urban commoners.

Chikamatsu’s Contribution to Japanese Theater

Chikamatsu’s most enduring legacy lies in his transformation of Japanese theater into a powerful medium for exploring human emotion and societal constraints. His contributions to both Bunraku and Kabuki were profound, though his work in Bunraku is especially revered. He refined the art of jōruri, the narrative chanting used in Bunraku, and tailored his scripts to suit the stylized movements and symbolic storytelling of puppetry.

His plays are often categorized into two major genres: sewamono (domestic dramas) and jidaimono (historical dramas). In sewamono, Chikamatsu focused on the lives of commoners, delving into personal struggles and emotional conflict. These plays often depicted the clash between personal desire and social obligation. In contrast, his jidaimono works drew from historical or legendary material, portraying samurai loyalty and political intrigue.

For Kabuki, Chikamatsu adapted many of his Bunraku scripts, infusing them with dynamic stagecraft, exaggerated gesture, and elaborate costumes. Yet, despite the stylistic differences between Bunraku and Kabuki, his core themes remained consistent: the moral dilemmas faced by individuals in a rigid society. Chikamatsu’s unique blend of realism, poetic language, and dramaturgical innovation set a new standard for theatrical writing in Japan.

Themes in Chikamatsu’s Plays

Chikamatsu’s plays consistently grapple with complex and often tragic themes. Chief among them is the conflict between giri (social obligation) and ninjō (personal feelings), a tension that underpins many of his most powerful works. This conflict often leads to the theme of forbidden love, especially in his domestic tragedies.

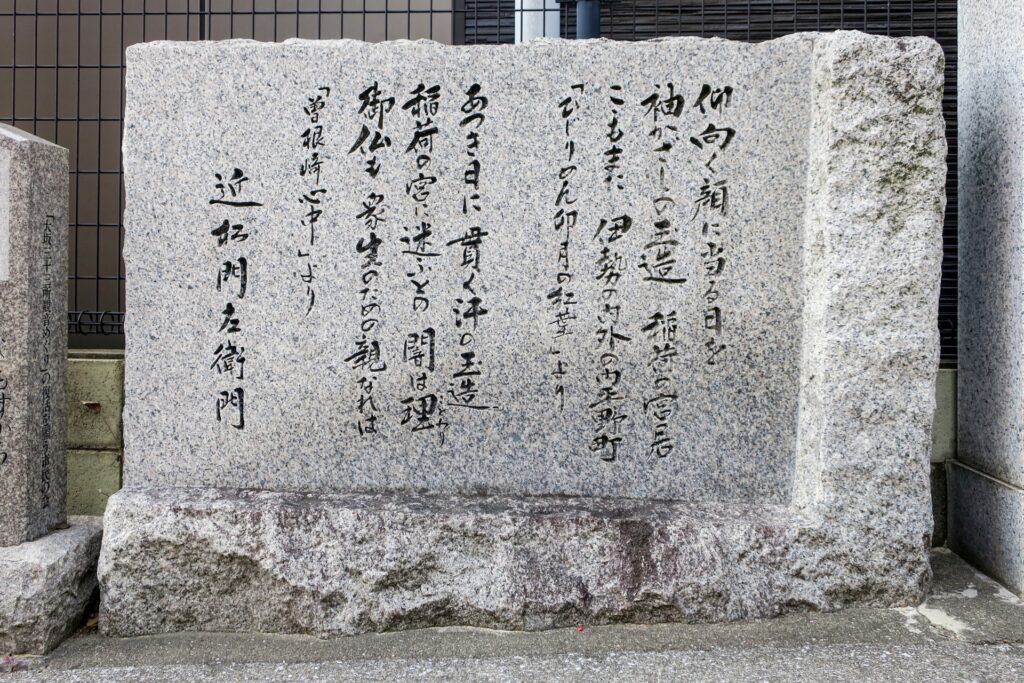

One recurring narrative is the shinjū, or double suicide pact, where lovers take their own lives rather than be separated by societal pressures. “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki” and “The Love Suicides at Amijima” exemplify this theme, portraying young couples whose devotion is crushed by economic hardship and rigid class structures. These tales offer both a critique and a reflection of Edo-period social values.

Other plays examine loyalty, betrayal, and the consequences of personal ambition. In his historical dramas, Chikamatsu explores the psychological costs of war and the fragile nature of political power. Despite being rooted in 18th-century Japan, his characters are emotionally accessible to modern audiences, highlighting universal human experiences.

Chikamatsu and Shakespeare: A Cross-Cultural Comparison

Chikamatsu Monzaemon is frequently referred to as the “Shakespeare of Japan,” and the comparison is apt in many ways. Like Shakespeare, Chikamatsu possessed an uncanny ability to capture the full range of human emotion, from romantic longing to existential despair. Both playwrights operated within thriving theatrical cultures and produced a diverse body of work that blended tragedy, comedy, and history.

Structurally, Chikamatsu’s plays mirror Shakespearean drama in their use of intricate plots and deep character development. Where Shakespeare employed soliloquies to reveal inner turmoil, Chikamatsu used the narrator’s chant in Bunraku to convey emotional depth and context. Both dramatists explored themes of fate, love, power, and mortality, often portraying characters trapped by forces beyond their control.

Culturally, each writer left an indelible mark on their respective literary canons. Shakespeare shaped the English language and theatrical tradition, while Chikamatsu elevated Japanese popular theater into a serious art form. Their works continue to be studied, performed, and reinterpreted globally, making them timeless figures in world literature.

A Guide to Chikamatsu’s Most Famous Works

Chikamatsu wrote over 100 plays, but a few stand out as enduring masterpieces. Below is a selection of his most famous works, categorized by genre, theme, and year.

| Title | Year | Genre | Summary |

| The Love Suicides at Sonezaki | 1703 | Sewamono | A tragic tale of lovers bound by duty and fate. |

| The Battles of Coxinga | 1715 | Jidaimono | A historical epic about loyalty and war. |

| The Love Suicides at Amijima | 1721 | Sewamono | A story of doomed lovers caught in societal traps. |

The Love Suicides at Sonezaki was inspired by a real-life double suicide and marked a turning point in Chikamatsu’s career, bringing emotional realism to the stage. The Battles of Coxinga is a grand historical drama depicting the hero Koxinga’s fight to restore the Ming dynasty. The Love Suicides at Amijima, considered one of Chikamatsu’s most refined tragedies, continues to captivate audiences with its psychological complexity.

These plays not only entertained but also stirred moral reflection among Edo-period audiences, making them critical texts for understanding Japanese culture and society. Notably, “The Love Suicides at Sonezaki” has seen renewed interest in Japan following its appearance in the recent film adaptation of “Kokuhou” (National Treasure), demonstrating how Chikamatsu’s works continue to inspire and captivate new generations.

Chikamatsu in the Modern World

Chikamatsu’s influence extends well beyond Edo-period Japan. His plays have been translated into multiple languages and performed on stages across the globe, including notable adaptations in English-speaking countries. His emotionally rich narratives and universal themes resonate with contemporary audiences, making his work a frequent subject in academic and theatrical circles.

Modern directors often reinterpret Chikamatsu’s work through various lenses—feminist, psychological, or political—highlighting their adaptability and depth. His portrayal of the oppressed individual in a rigid society speaks directly to modern concerns about identity, freedom, and systemic inequality.

In academia, Chikamatsu is studied not only for his literary merit but also for his cultural insight into Tokugawa-era Japan. His work serves as a bridge for intercultural understanding, especially in courses on world literature, Japanese history, and comparative drama.

Conclusion: Chikamatsu’s Universal Legacy and Future Relevance

Chikamatsu Monzaemon rightly holds the title of “the Shakespeare of Japan.” His mastery of dramatic form, emotional resonance, and social commentary has secured his place as a cornerstone of Japanese literature and theater. Through both Bunraku and Kabuki, he gave voice to the marginalized, questioned societal norms, and captured the profound struggles of the human heart.

Today, his plays continue to be taught in classrooms, adapted on international stages, and revered by scholars and artists alike. As global audiences seek narratives that explore identity, morality, and emotional truth, Chikamatsu’s works remain remarkably relevant. His legacy endures not only as a historical figure but as a living influence in the ever-evolving world of theater and storytelling.