The Kamakura Period, spanning from 1185 to 1333, marked a revolutionary shift in Japanese governance and society. With the rise of the samurai and the establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate, Japan transitioned from imperial aristocracy to a military-led government. This era also witnessed the spread of new forms of Buddhism, the Mongol invasions, and profound changes in art and culture. This article explores the key political, cultural, and societal dynamics of the Kamakura Period and its enduring legacy.

Overview of the Kamakura Period

The Kamakura Period (1185–1333) marks a crucial turning point in Japanese history. This era saw the decline of the aristocratic Heian court and the emergence of a new political order led by the warrior class. Following centuries of imperial dominance, power shifted dramatically when Minamoto no Yoritomo established a military government in Kamakura, inaugurating Japan’s first shogunate. This military regime, known as the bakufu, coexisted with the imperial court in Kyoto but held real political authority.

During this era, Japan experienced significant political decentralization, cultural shifts, and the institutionalization of feudalism. The Kamakura Period is often regarded as the beginning of Japan’s medieval age, where samurai warriors became the central figures of governance, warfare, and cultural patronage. From military innovations to religious transformations, this period laid the foundation for much of Japan’s later development.

The Rise of the Samurai Class

The emergence of the samurai class was both a cause and a consequence of the Genpei War (1180–1185), a civil conflict between the Taira and Minamoto clans. The victory of the Minamoto, led by Yoritomo, not only concluded decades of aristocratic rivalry but also legitimized the power of the warrior elite. These samurai warriors, bound by loyalty and military service, became the backbone of the new feudal system.

Unlike the court nobles of the Heian era who prized literature and refinement, the samurai class valued martial skill, discipline, and loyalty. The conflict reshaped societal values and solidified the role of military families in Japanese governance. The success of the Minamoto clan established a precedent for military rule that would define Japan for centuries.

The Establishment of the Kamakura Shogunate

In 1192, Minamoto no Yoritomo was granted the title of “Sei-i Taishōgun” (barbarian-subduing generalissimo) by the emperor, officially marking the start of the Kamakura Shogunate. Yoritomo’s government was headquartered in Kamakura, far from the imperial court in Kyoto, which symbolized the geographical and ideological divide between civil and military authority.

The Kamakura Shogunate instituted a dual governance structure: while the emperor remained a symbolic figurehead, the shogun wielded actual political and military power. Key administrative positions included the shikken (regent, especially during the Hōjō regency), gokenin (vassals), and various provincial governors who managed land and justice.

This new system allowed for more direct control over the provinces and helped stabilize governance through a rigid hierarchy of loyalty and land-based reward. The Kamakura regime laid the foundation for Japan’s feudal structure that persisted into the Edo Period.

Major Political Events and Conflicts

Several significant conflicts defined the Kamakura era. One of the earliest was the Jōkyū War in 1221, in which Emperor Go-Toba attempted to reclaim power from the shogunate. His defeat reaffirmed the military government’s dominance and led to increased centralization under the Hōjō regents.

The Mongol invasions in 1274 and 1281 posed an unprecedented external threat. Led by Kublai Khan, the invasions were repelled with the help of typhoons—the legendary kamikaze or “divine wind”—but at great economic and military cost. Though Japan avoided conquest, the strain of constant readiness undermined the Kamakura government.

These conflicts not only tested Japan’s military resilience but also fostered a sense of national unity and identity, reinforcing the samurai’s importance in society.

Religion and Cultural Flourishing

The Kamakura Period was also a time of profound religious transformation. The turmoil and warfare of the age inspired new forms of Buddhism that were more accessible to common people and suited to the warrior ethos.

Zen Buddhism gained popularity among the samurai for its emphasis on discipline, meditation, and inner strength. Pure Land Buddhism (Jōdo-shū), which taught salvation through devotion to Amida Buddha, attracted both elite and commoners. Nichiren Buddhism, with its focus on the Lotus Sutra and national salvation, became politically influential.

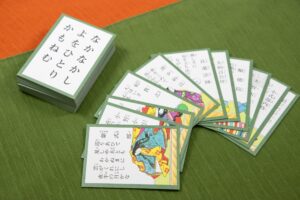

The religious landscape diversified, and temples became not only places of worship but also centers of education and artistic patronage. Iconic religious sites such as the Great Buddha of Kamakura (Kamakura Daibutsu) and Tsurugaoka Hachimangū Shrine exemplify the architectural achievements of the era. Literary works also flourished, including Hōjōki and Heike Monogatari, reflecting the impermanence of life and the valor of warriors.

Art, Architecture, and Daily Life

Kamakura art reflected a shift from the ethereal elegance of the Heian period to a more realistic and dynamic style. Sculptors like Unkei and Kaikei produced statues with intense expression and anatomical accuracy, often depicting Buddhist deities and historical figures.

In daily life, the samurai lifestyle emphasized austerity and discipline, in contrast to the courtly opulence of previous centuries. Common foods included rice, fish, and seasonal vegetables. Clothing was simpler and more functional, especially for the warrior class. Customs like archery and horseback riding became both martial training and cultural practices.

| Aspect | Heian Period (Aristocrats) | Kamakura Period (Samurai) |

| Governance | Court bureaucracy | Military rule |

| Art Style | Delicate, elegant | Realistic, dynamic |

| Religion | Esoteric Buddhism | Zen, Pure Land, Nichiren |

| Lifestyle Focus | Poetry, ceremony | Martial skill, simplicity |

Decline of the Kamakura Shogunate

The stability of the Kamakura Shogunate began to erode in the 14th century. After the death of Yoritomo, the Hōjō clan assumed regency and exercised real power. However, their rigid rule and failure to adequately reward vassals, especially after the Mongol invasions, bred resentment.

In 1333, Emperor Go-Daigo launched the Kenmu Restoration to restore imperial rule. With the help of disaffected samurai like Ashikaga Takauji, the Kamakura regime was overthrown. Though short-lived, the Kenmu Restoration marked the official end of the Kamakura Shogunate and ushered in the Muromachi Period under the Ashikaga Shogunate.

Legacy of the Kamakura Period

The Kamakura Period left an indelible mark on Japanese history. It solidified the samurai’s role as Japan’s ruling class and institutionalized a feudal system based on loyalty and land tenure. The political decentralization pioneered by the Kamakura Shogunate would influence Japan’s governance for centuries.

Samurai values like loyalty (chu), courage, and honor began to crystallize into the bushidō code, which would later become central to Japanese identity. Kamakura Buddhism, especially Zen, influenced aesthetics, from garden design to martial arts. The legacy of this period continues to shape Japan’s cultural and political landscape.

FAQs About the Kamakura Period

What is the Kamakura Period known for? The Kamakura Period is known for the rise of the samurai, the establishment of Japan’s first military government, and the spread of new Buddhist sects like Zen and Pure Land.

Who ruled during the Kamakura Period? Although emperors remained in Kyoto, real power was held by the shogun in Kamakura, particularly under the Minamoto and later the Hōjō regency.

What ended the Kamakura Shogunate? The Kamakura Shogunate ended in 1333 when Emperor Go-Daigo successfully overthrew the regime with the help of discontented warriors, initiating the brief Kenmu Restoration.

Additional Insights: Kamakura in Modern Culture & Travel

The Kamakura Period continues to inspire modern media, appearing in games such as Ghost of Tsushima and historical films. The era’s themes of loyalty, warfare, and spiritual resilience resonate deeply in storytelling.

Travelers can explore Kamakura city, which retains many historical landmarks. Notable sites include:

- Tsurugaoka Hachimangū: The central shrine of the Kamakura Shogunate.

- The Great Buddha (Daibutsu): A massive bronze statue and iconic representation of Kamakura Buddhism.

A walking tour through Kamakura reveals a blend of coastal scenery, spiritual heritage, and samurai history. Visitors can also enjoy local delicacies and traditional crafts along Komachi Street.

Conclusion: Why the Kamakura Period Still Matters

The Kamakura Period stands as a transformative epoch in Japanese history. It shifted political power from imperial courtiers to military rulers, laid the groundwork for feudal governance, and nurtured religious and cultural currents that endure today.

Understanding the Kamakura Period provides insight into Japan’s evolution from courtly elegance to martial discipline. Its legacy is visible in modern Japanese values, institutions, and aesthetics.

To understand today’s Japan, we must first understand Kamakura.