Japanese seating etiquette is rooted in centuries of cultural tradition and remains relevant in both formal and informal settings today. Whether you’re attending a business meeting, dining at a traditional restaurant, riding a taxi, or stepping into an elevator, knowing how and where to sit (or stand) can show deep respect for the culture. This guide covers everything from formal “kamiza” and “shimoza” systems to practical modern applications in daily life.

Introduction to Japanese Seating Etiquette

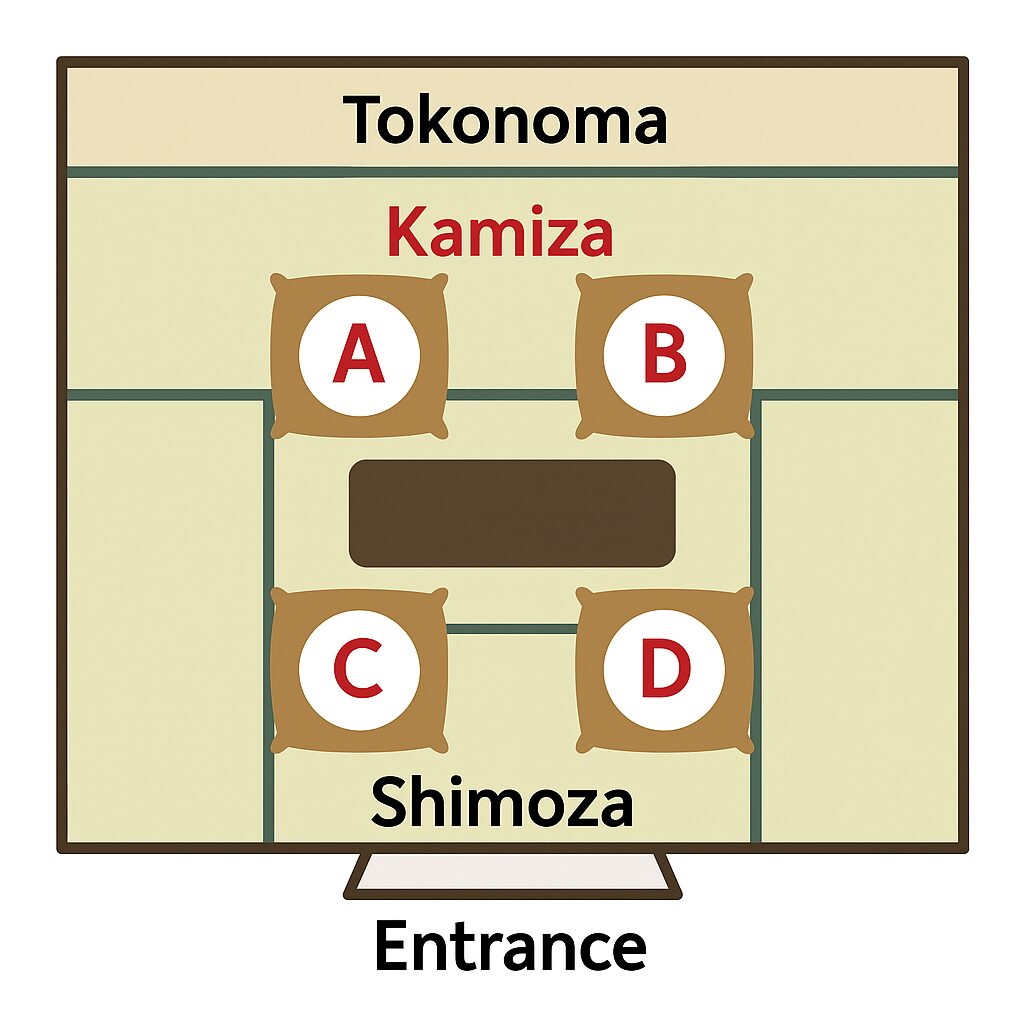

In Japanese culture, seating etiquette is more than just choosing a place to sit; it is a way of showing respect, acknowledging hierarchy, and maintaining social harmony. Knowing where and how to sit in various settings can leave a lasting impression, especially in business and formal environments. Terms such as kamiza (seat of honor), shimoza (lower seat), and seiza (formal kneeling posture) form the cornerstone of Japanese seating norms. For example, the kamiza is typically reserved for the highest-ranking individual and is usually the seat farthest from the door. The shimoza, in contrast, is located nearest to the entrance and is generally taken by junior members or guests. In traditional tatami rooms, these rules are even more pronounced, with room orientation and formality dictating appropriate posture and placement. Understanding these customs allows visitors and residents alike to navigate Japanese social settings with grace and cultural sensitivity.

Key Seating Positions and Their Meanings

Kamiza and Shimoza in Formal Settings

In formal environments such as business meetings and ceremonial events, the concept of kamiza and shimoza plays a central role. In a rectangular table layout (commonly referred to as the “ロ” shape), the kamiza is the seat furthest from the door—a symbol of protection and honor. In a U-shaped or “コ” layout, the kamiza typically occupies the center-back position, again furthest from the entrance.

Westerners might be used to the right-hand side as a position of superiority, but in Japan, the left is often considered higher in rank—especially in formal events like tea ceremonies. Such contrasts can cause confusion, which is why it’s critical for foreign visitors to understand the Japanese context. Business etiquette demands careful adherence to these norms to avoid unintentionally offending clients or superiors.

Determining Seating Order: The Priority Rule

Assigning seats in Japan follows a clear hierarchy, usually based on a combination of job title, company seniority, and age. A high-ranking but younger executive may be prioritized over an older, lower-ranking employee. These nuances are especially important in business meetings or corporate dinners. For instance, in a client meeting, the highest-ranking person from the guest side is given the kamiza, while the host’s most junior member may sit in the shimoza position closest to the door. Conflicts in ranking are resolved through social consensus, often with subtle negotiations and deference.

When in Doubt: Ask the Staff

If you’re ever unsure about where to sit, the best course of action is to politely ask a staff member or host. In Japanese culture, displaying cultural sensitivity and humility often earns more respect than rigidly adhering to rules. Phrases like “Dochira ni suwattara ii deshou ka?” (どちらに座ったらいいでしょうか? – “Where should I sit?”) show your willingness to follow local customs, even if you are unsure.

Common Seating Arrangements at Restaurants

In restaurants, particularly traditional venues such as izakayas or ryotei, the seat farthest from the entrance is usually the kamiza. If a host is present, they will often guide guests to their appropriate positions. In casual settings, this rule is more flexible, but it’s still polite to offer the most comfortable or advantageous seat to the most senior person in your group. In modern restaurants, staff may also take seating hierarchies into account when assigning tables.

Traditional Japanese Sitting Styles

Seiza: The Formal Sitting Posture

Seiza is the quintessential Japanese way of sitting: kneeling with your legs folded under your thighs, back straight, and hands resting on the lap. This posture is common in formal settings such as tea ceremonies, weddings, funerals, and certain martial arts. While it reflects discipline and respect, it can be physically demanding, especially for those not accustomed to it. Alternatives like agura (cross-legged sitting) or sitting on a cushion (zabuton) are sometimes accepted, particularly for elderly individuals or foreigners. Nonetheless, making an effort to sit in seiza, even briefly, demonstrates cultural awareness.

Modern Norms and Exceptions

Contemporary Japanese society has evolved, and so have its seating customs. Younger generations are increasingly relaxed about traditional rules, especially in informal settings. Gender roles in seating have also become more fluid, and regional variations can influence etiquette. For instance, in Tokyo, adherence to formal norms may be stricter than in Osaka. It’s important to remain observant and flexible, adapting your behavior based on cues from the people around you.

Common Mistakes Foreigners Make

Foreign visitors often commit minor social blunders when navigating Japanese seating etiquette. Common mistakes include:

- Sitting before being invited

- Accidentally taking the kamiza

- Crossing legs or stretching out in a formal tatami room To recover, simple phrases like “Sumimasen, wakarimasen deshita” (すみません,わかりませんでした – “I’m sorry, I didn’t know”) can help. Japanese hosts are generally understanding if you show humility and a willingness to learn.

Cultural Insights Behind the Etiquette

Japanese seating etiquette is deeply tied to cultural values like respect (sonkei), hierarchy (joushige kankei), and harmony (wa). These values are reflected in everything from where one sits to how they sit. The origins can be traced back to samurai traditions and tea ceremony rituals, where posture and position conveyed loyalty and rank. Even today, these values underpin Japanese interpersonal interactions, making seating etiquette a window into the national character.

Everyday Scenarios: Seating Etiquette in Elevators and Taxis

Elevator Etiquette: Where You Stand Matters

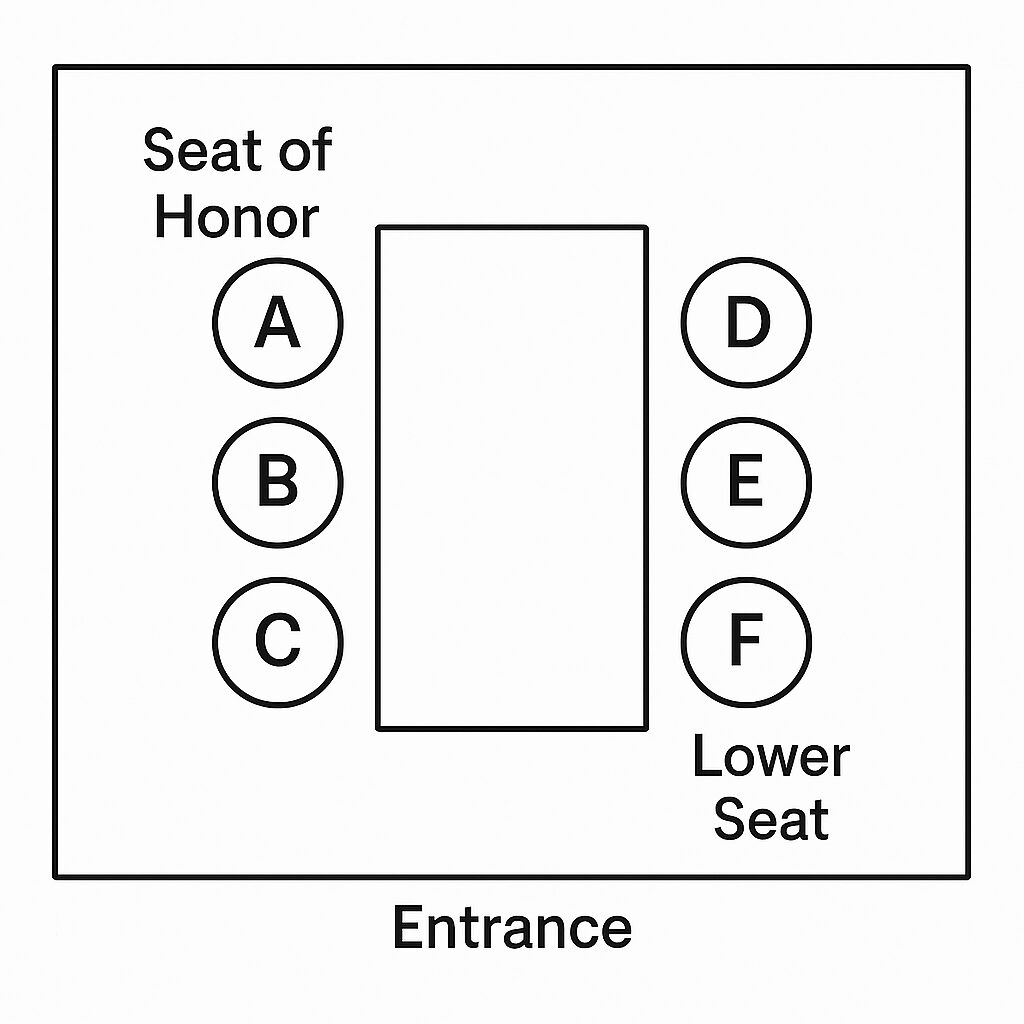

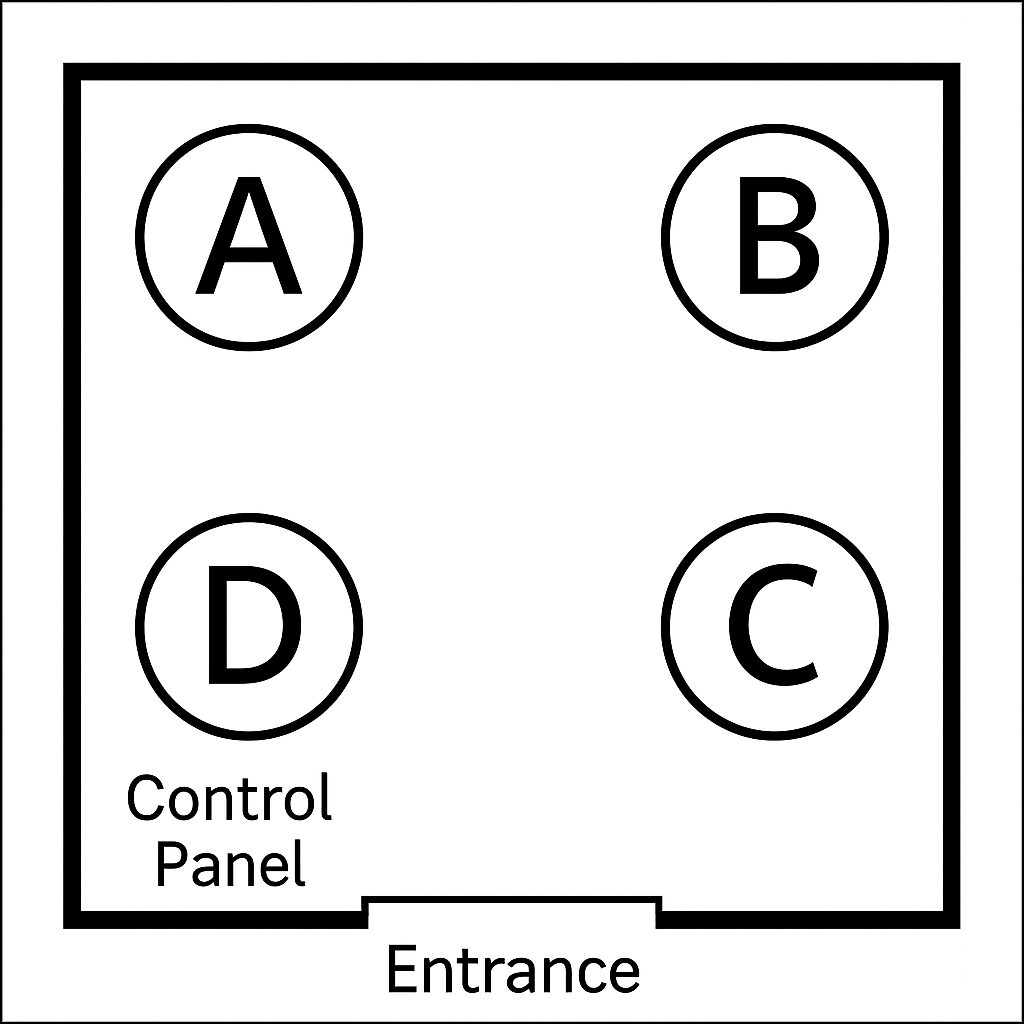

Elevators in Japan also observe unspoken seating hierarchies. The most senior person stands at the farthest corner from the door (the kamiza), while the junior member stands closest to the control panel (the shimoza), expected to operate the buttons. For example, in a business setting, a junior employee should enter first to hold the door and manage the controls, allowing seniors to enter and exit comfortably.

Taxi Etiquette: Not All Seats Are Equal

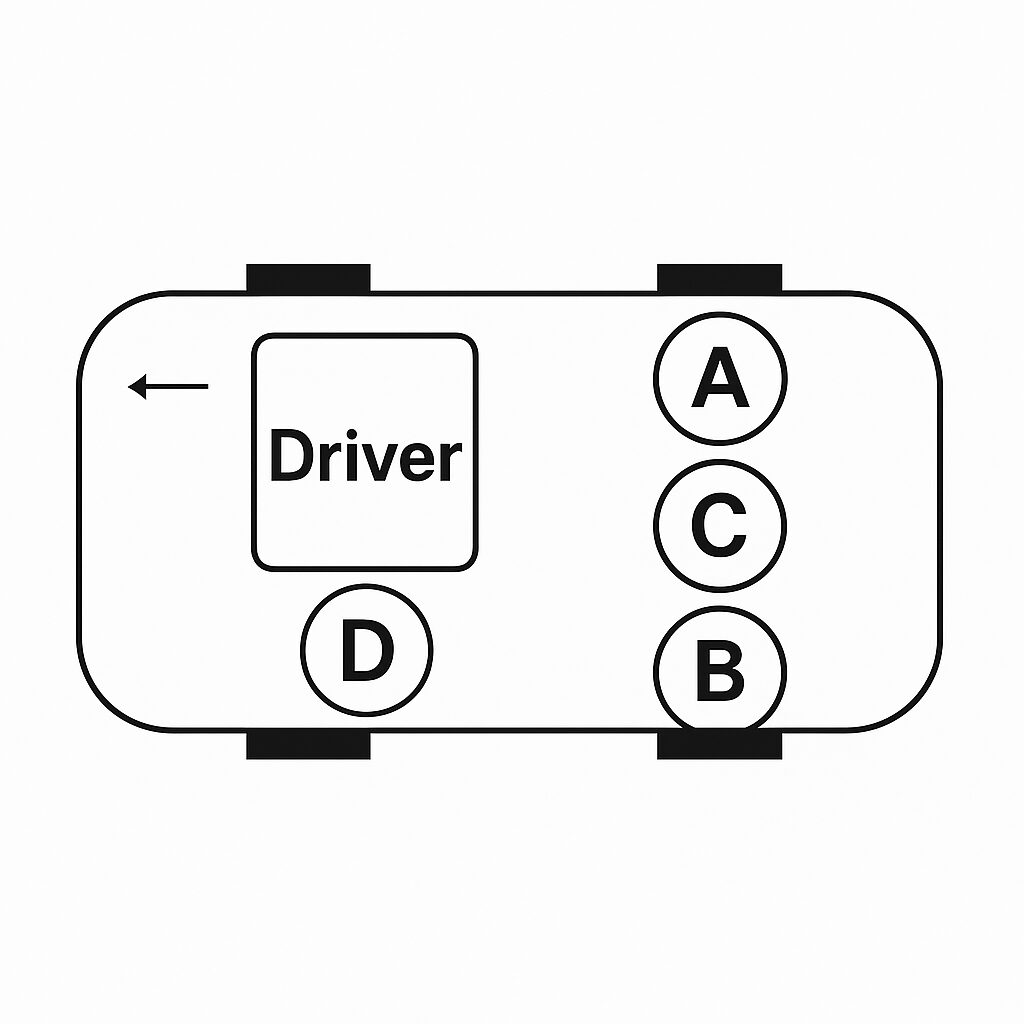

In a Japanese taxi, the seat directly behind the driver is considered the kamiza and is reserved for the most senior person. The front passenger seat is the shimoza, often taken by a junior staff member or assistant. However, practical exceptions exist—for example, safety concerns or instructions from the driver. If in doubt, it’s always polite to ask, “Where should I sit?”

Visual Guide to Japanese Seating Arrangements

- Tatami Room: Kamiza is the spot farthest from the entrance, often near the alcove (tokonoma). Shimoza is closest to the door.

- Business Table (Rectangular): Kamiza is the farthest seat from the door. Shimoza is closest to the entrance.

- Taxi: The top seat is behind the driver’s seat. The bottom seat is the passenger seat.

- Elevator: Kamiza is the position behind the control panel. Shimoza is the position in front of the control panel.

Conclusion: Showing Respect Through Where and How You Sit

Japanese seating etiquette embodies the country’s core values of respect, hierarchy, and harmony. Understanding where and how to sit—whether in a boardroom, a restaurant, or a taxi—can enhance your cultural fluency and interpersonal relationships. While mistakes may happen, demonstrating a willingness to observe, ask questions, and adapt will always be appreciated. In Japan, effort and humility matter more than perfection.